Building for Bathing

- | Hannah Parham

Water is not the architect’s friend. The detrimental effects of water on fabric mean that buildings can quickly deteriorate if they are not properly maintained. Water has presented a particular challenge to two designers at Insall – Libby Watts and Simonette Doig – who have been working on historic swimming pool buildings this year.

Yet everyone loves water! Its therapeutic properties have long been recognised and celebrated: think of the thermal springs at Bath, still in use today, partly in new and refurbished buildings by Donald Insall Associates. Water is gentle on the body, allowing people of all ages and different degrees of physical prowess to participate in exercise. Swimming keeps your heart rate up but takes the stress of impact off your body; it builds endurance, muscle strength and cardiovascular fitness; swimming makes you feel happier and less anxious. Everyone loves swimming!

So water in buildings is both a heritage headache and the soul’s delight. For these reasons, Insall relishes the challenge of conserving public bathing buildings. Presently, the practice is working on three bathing pools, one defunct and two partially in use, but all in sharp need of repair. We hope to revive them for full public benefit and enjoyment.

Bathing in Birmingham

The most flamboyant in its architecture is the Moseley Road Baths in Birmingham, built in 1907 by architect William Hale and Son, listed at Grade II*. This is one of the most celebrated Victorian/Edwardian-era municipal bathhouses in the country. It originally provided laundries, ‘slipper’ baths for private individual bathing (essential in an era when many homes did not have bathrooms), and three public pools (hierarchically arranged, in true Edwardian fashion: men’s first class, men’s second class and women’s). In the winter the men’s second class was boarded over and used for dances, concerts and social clubs. The degree of preservation at Moseley Road is extraordinary and includes the complete set of slipper baths, the oak ticket offices and attendants’ kiosks, and possibly the only surviving steam-heated drying racks in a British swimming pool.

Insall is neck-deep into the first stage of a phased repair programme. The project faces considerable technical challenges and, after site surveys, investigations and opening up, we are moving forward in close collaboration with Historic England, the local conservation officer, the National Trust and World Monuments Funds, among other stakeholders. Inspection has highlighted that condensation has caused decay to both the cast iron and timber soffits within the principal Gala Pool, particularly relative to the clerestory windows. Chemicals present in the pool environment have exacerbated decay; control of cold bridging, interstitial condensation, insulation, ventilation and drainage of condensate all require careful consideration. Enabling work involved a measured survey, removal of pigeon guano, an ecological study, and asbestos investigations before the work proper could commence.

Normally the first thing we would do when undertaking roof repairs would be to construct a temporary roof over the original roof to protect it, but in this instance, given that a pool environment is designed to be resilient to water, we decided this would be superfluous. This has saved considerable resource, in this coalition-funded project, and had no negative impact on the fabric.

The project is overseen by Matthew Vaughan, who leads our Birmingham office, but on his own admission the greater credit is due to Libby Watts, a Part II Architectural Assistant who has recently qualified as an architect at Birmingham School of Architecture, with distinction, having used her experience on the project as a case study.

Swimming in Swindon

The second project is a building of the same era, initially erected in 1891 by and for railway workers of the Great Western Railway and listed at Grade II. The Swindon Health Hydro (its modern moniker) was a unique complex for its time, originally both a medical dispensary and swimming baths, and was financed by company workers’ contributions to a pioneering health insurance scheme, the GWR Health Fund Society.

The building was designed by a local architect J J Smith and constructed from materials largely manufactured by the GWR Works in Swindon. It was considered one of the most up-to-date facilities of its kind when it was opened, and remains ahead of its time in providing – as it originally did – facilities for both prevention of disease (the baths) and cure (the dispensary), side-by-side. On the nationalisation of the railways it passed to British Railways (Western Region) and then finally to Swindon Borough Council. It has been very little changed internally and the two Victorian swimming baths survive in almost original condition, their wrought iron trusses recalling a vast Victorian train shed. The Hydro remains in use and largely for its intended purpose as a health, fitness and wellbeing centre, including the original and oldest Victorian-style Turkish Baths, but its future is uncertain.

Insall was commissioned to produce a Conservation Management Plan for the Swindon Health Hydro, to investigate and record the building, to develop a series of conservation policies, and then produce an appraisal examining options for continuing, sustainable use. Again, one of the younger members of the Practice, architectural assistant Simonette Doig, has under taken a key role alongside, in earlier stages of the project, the late Peter Carey.

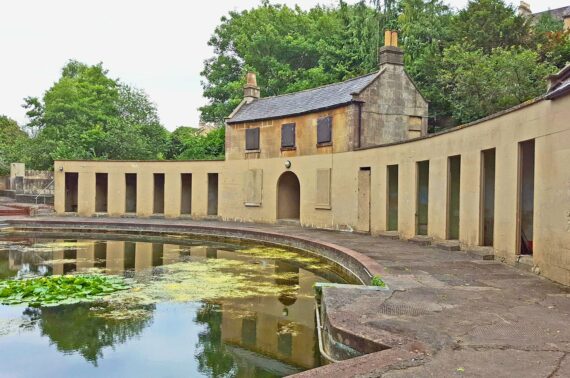

Bath

The same team, with David Barnes, leads the final aquatic project in the office. This concerns the oldest, open air public swimming baths in the country, listed at Grade II*. The Cleveland Pools in Bath were created in 1815 as a discreet adaptation of the natural swimming facilities provided by the adjacent river Avon. The crescent-form building was contemporary with some of the final phases of the Georgian expansion of Bath, and is in the simple classical style for which the World Heritage city is famous.

The original arrangement included a river-fed main pool for male bathers, whose activities had been somewhat curtailed by the 1801 Bathwick Water Act which prohibited nude male swimming in the river. There was also a smaller, separate, spring-fed ladies’ pool, screened and enclosed by a high wall. The Pools suffered fluctuating fortunes over the centuries, but remained in largely continuous use until 1984. After a brief period as a trout farm, the Pools were abandoned in 2003.

In December 2018, the National Lottery Heritage Fund awarded the Cleveland Pools Trust £4.7 million. Insall is leading a multi-disciplinary design team at delivery stage to restore the complex as a community pool. The redundant Council-owned site is currently on the Heritage at Risk register. The project will conserve the Georgian buildings and upgrade the facilities to allow for year-round swimming and other wellbeing related activities. The pools will be naturally treated and heated using a water-source heat pump. When complete, there will be a 25-metre swimming pool, children’s pool and kiosk, along with the necessary ancillary facilities. Cleveland Pools is currently programmed to reopen to the public in 2021.

In his seminal account of swimming in Britain, Waterlog, Roger Deakin captured the magic of water:

… you can breath and move in perfect rhythm, so the music takes over. Mind and body go off somewhere together in unselfconscious bliss, and the lengths seem to swim themselves. The blood sings, the water yields; you are in a state of grace, and every breath gets deeper and more satisfying … if you tread on air on your way from the pool, it is because you are floating somewhere just above your corporeal self.

Everyone loves swimming! And hopefully, as a result of Insall’s work at three of fine public swimming baths, we can keep the water away from the building fabric and safely in the swimming pools, so all can take the plunge towards a greater equilibrium of wellbeing of the mind, body and soul.