Conserving ‘Pleasing Decay’: The Bristol Colonnade, Portmeirion

- | Elinor Gray-Williams

We are lucky in Wales to live in a country so totally diverse. The country’s modern buildings and landscapes are typically defined by the heroic achievements of people through industry. These contrast with gentler expressions of human endeavour, and nowhere so distinctively as amid the slate mining landscape of Blaenau Ffestiniog where, in the 20th century, the magical Italianate village of Portmeirion was created.

Portmeirion was built by the architect Clough Williams-Ellis (known to his peers and followers as ‘Clough’) between 1925 and 1975, before his death in 1978. Clough intended to show how a beautiful site could be developed without spoiling it. He created a landscape of anachronisms: the whole site was an exercise in historic restoration, with many buildings destined for demolition elsewhere dismantled and reconstructed here. The Bristol Colonnade is one of the highlights, towering proud in the Italianate landscape above the main Piazza.

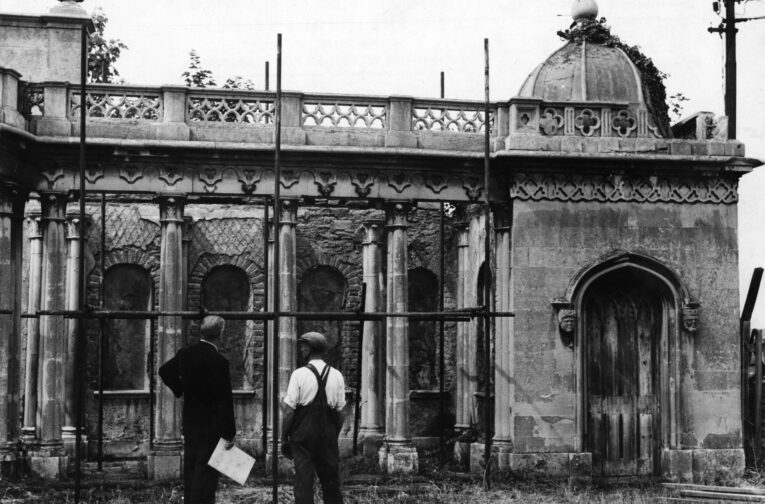

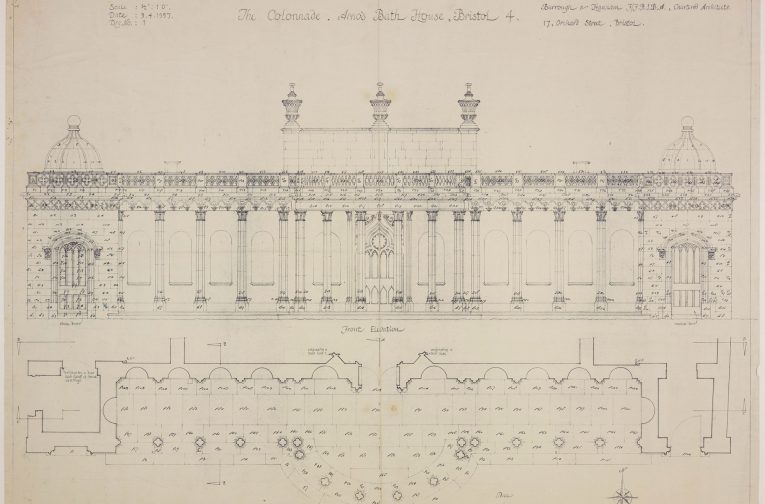

The Colonnade was originally built in 1760 by James Bridges, and stood at the front of a Bristol bathhouse. It was damaged by wartime bombs and had fallen into disrepair when, in 1959, Clough carefully measured and recorded it, following which he disassembled and moved each piece of delicate masonry, transporting them so that they could be re-built in North Wales by his master mason, Mr William Davies. Clough recalls: ‘First to last, in Bristol as well as at Portmeirion, it was almost entirely a matter of high masonry craft, for, having determined its site and fixed its levels, there was little more for me to do but look on, approve and very much admire’.

Donald Insall Associates was invited to inspect the Colonnade following concerns over the condition of the masonry, which is compromised in some areas of the underside of the structure, and at the front.

At present we are unsure if the damage to the front was caused by pollution when the building was in Bristol, or another factor. Historic photos of the building in its original location can help us make some assumptions, but it has been difficult to assess.

We have been trialling repair and cleaning methods to establish an appropriate conservation approach. Trials have shown that gentle and non-destructive methods of cleaning can be used, undertaken largely by hand. Similarly, some of the pointing mortar is hard, and damaging to the stonework: again, trials have been undertaken to determine the extent to which this mortar can be removed and renewed without damaging the masonry.

Clough Williams-Ellis inspecting the Bristol Colonnade c. 1957-8. Image courtesy of Portmeirion Village.

Ornaments of time

There are interesting considerations for the next stage of the Colonnade’s conservation. The authenticity of the structure (it was moved from Bristol), and of Portmeirion itself, is multi-layered. It is not easy to define the final approach, as this in turn demands assessment of some complex criteria, namely significance, construction methods and surface appearance. We have taken time to look at and to assess what is special about the identity of the structure and site. The trials have certainly proven conclusive as to how we can go about repairing the structure, but there are many questions to be asked before we proceed. These questions include that of: do we make good, or do we remedy previous errors to make better?

Clough was a master of illusion, delight and deception, but there are problems with how the structure was originally pieced together that mean we have to decide whether to implement corrective measures to remedy the defect, or accept that there will always be ongoing difficulties.

One such example, and forming one of the more significant aspects of the trialling stage, is to investigate the substrate materials of the floor structure. Limited and non-destructive investigation has shown that the substrate has no damp-proof membrane within the concrete plank construction. Consequently, water penetrates through cracks within the concrete deck and causes decay to the stonework below.

We seek to avoid blindly imposing a conservation approach that regards ‘authenticity’ as forever retaining the original defective fabric, but removing the deck would prove far too destructive.

Drawing of the Bristol Colonnade by Burrough and Hannam of Bristol. Image © RIBA.

The likelihood is that we will need to devise a strategy to control this water ingress by other means, and patch-and-repair any consequential damage on a regular basis to stave off long-term failure. There are also interesting considerations in relation to how we repair ‘pleasing decay’.

There is obvious damp penetration through the back wall of the structure and this is causing deterioration of the vibrant paint finishes, something we need to remedy. Yet the romance of the antiquated, worn and damp surfaces was attractive to Clough, and he often specified two shades of paint for his colour schemes ‒ dark at the bottom and lighter at the top ‒ to mimic a ‘historic’ look. The porous stone of the Colonnade is in immediate contact with the penetrating damp behind, and from the leaking deck above. While we seek to fix this problem, we must also respect the significance of Clough’s aesthetic approach.

Conservation can never be an exact science and it is important to assess what is special about any building or setting before agreeing a way forward. There are major complexities in considering appropriate approaches for repairs at Portmeirion. This is particularly so in relation to structures that have been lifted out of their original context and re-defined as architectural follies, often with elements of ‘pleasing decay’ intended as a significant factor for the aesthetic. These complexities are then compounded further still when said structures have been made into such personal landscapes with a bold character and background as infused by Clough.

Romantic landscapes

When considering repairs, we refer to other projects where we have experience of working with other romantic landscapes with similar complexities.

Our work at the Gothic Folly at Wimpole in Cambridgeshire is instructive. Here, we reinstated lost detail of the 18th-century structure based on archival drawings and archaeological analysis. Restoration might seem a perverse approach to a ‘designed ruin’, but it halted the process of decay which had gone long beyond ‘pleasing’. Our work has led to greater appreciation of the original picturesque design, which sits in a landscape by Capability Brown. The judges who awarded the project a Europa Nostra award noted that the ‘clever restoration’ had ‘inspire[d] thought about the nature of conservation’.

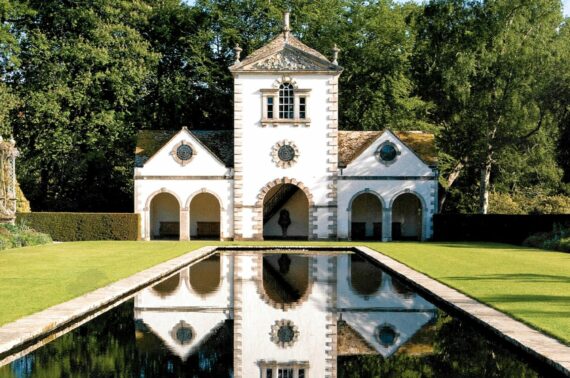

Our work to repair the fabric of the Pin Mill at Bodnant Gardens is another good example, as this is another restored and re-built historic building in a fine landscape. At Bodnant, we took a pragmatic approach to retaining the Pin Mill’s identity, again considering that it is one of the signature elements within the National Trust’s gardens in Conwy.

Similarly, at Portmeirion, we will first and foremost consider the work which is necessary to improve the defect-prone constructional errors made by Clough; otherwise, we compromise the longevity of the structures, and ultimately diminish the delight they bring to visitors. We will, in parallel, seek also to protect the attraction of ‘pleasing decay’ where we can, and where it forms a significant factor for the aesthetic, as intended by the architect.

When Donald Insall was writing The Care of Old Buildings in the 1970s, he met Clough Williams-Ellis and thought him to be ‘a delightful one-off’. Clough might not be considered an exemplar of conservation architecture, but, as Donald put it to me, ‘that did not matter’.