Medieval Meets Modern: the Encaustic Tiles of the Palace of Westminster

- | Victoria Perry & Edward Lewis

With heavy use and exposure, even the most durable materials start to wear. The patina of time can be as interesting as the original finish, but deterioration can get to the point where any aesthetic value or meaning is obliterated. This presents a particular problem in buildings or objects where the significance of the design is greater than that of the fabric, such as the 19th-century encaustic tile floors in the Palace of Westminster.

Encaustic tile floors are found within the important sequence of spaces forming the entrance to the Victorian palace. These run from Westminster Hall, via St Stephen’s Hall, and via the circulation routes to and from the Central Lobby to the House of Commons and the House of Lords. The tiles are also used to floor the St Mary Undercroft Chapel, including the Members’ Entrance and the Peers’ Entrance, as well as for fireplace surrounds and on stairs. The floor designs form an integral part of the overall decorative scheme conceived by Charles Barry in the 1840s. The original encaustic tiles were created by Herbert Minton in the 1840s and laid from 1847. The artwork of each encaustic tile floor is specific to each space. Aside from considerable wear and tear, particularly to the floors, much of the interior survives as Barry intended, and has architectural and historic significance overall which transcends that of the floors alone.

By the turn of the 21st century, many of the tiles were nearing the end of their practical life, despite large areas having been replaced with often inferior quality tiles throughout the 20th century. In addition to our ongoing work on the Palace Courtyards and Westminster Hall, Donald Insall Associates is leading a project to repair these unique floors.

Fired Earth

Encaustic tiles are made from clay, which is one of the most time-honoured and widely used building materials on earth. However, the ubiquity of clay-based building materials such as bricks and tiles can sometimes blind us to the extraordinary physical and chemical qualities of this natural resource. Clays are naturally-occurring hydrous aluminium phyllosilicate minerals with feldspars and varying amounts of other material formed by the chemical weathering of rocks over millions of years. The minerals in clay trap water within their structure and form a flexible, partially water-resistant mass which becomes firm when dry. As a major constituent of many earth materials, clay forms the basis of traditional building materials including cob, daub, and earth floors, as well as the artificial linings of lakes, ponds and dams in a technique known as puddling.

Donald Insall Associates has worked on many projects where clay is used in its natural state, including the restoration of the lakes at Plumpton Rocks near Harrogate, wattle and daub panels at the Staircase House Museum in Stockport, and earth structures in the Middle East. Yet it is when dry clay objects are ‘fired’ ‒ heated to a very high temperature ‒ that the material magic really occurs: the molecular structures of the minerals change; any entrapped water (that remains after air drying to avoid rapid shrinking and failure) is released; the clay undergoes chemical changes including vitrification; it becomes ceramic.

Bricks and tiles, including clay roofing tiles and ‘quarry’ floor tiles, are perhaps the most familiar ceramic building materials. Brick and tile making in Britain are generally, as one would expect in a modern industrialised society, highly automated processes where much of the manual work of traditional production has been replaced by mechanisation. However, for repair and conservation projects, where short runs are needed, including those at the Palace of Westminster, tiles are still, or can be, made by hand.

The Potteries

Nowadays, most kilns are run on gas, which provides a controlled and reliable firing environment. During the 18th and 19th centuries, copious supplies of coal were necessary to produce bricks and tiles in increasingly large quantities. Consequently, the Midlands, where abundant supplies of clay and coal were found together, became one of Britain’s centres for industrial brick and tile making. Indeed, it was the particular skills and technological innovation found in north Staffordshire that provided the crucible for some of Britain’s finest architectural ceramics including cast terracotta or ‘faience’ and decorative encaustic tiles.

During the late 18th century, the towns which were to become the City of Stoke-on-Trent were renowned for their fine dinner and tea services made from Cornish white kaolin clays transported via the new canal network. Unlike traditional wheel-thrown pottery, this was mass-produced from a carefully-designed liquid clay and mineral suspension (a liquid body known as ‘slip’) which was cast in moulds. Rather than traditional craft skills, these new ‘manufactories’ needed specialists: scientists who could create and record experiments for new, better bodies and glazes, and artists, sculptors, painters and designers who could create new shapes, patterns and moulds. The Potteries became a crucible for creative talent.

One of the most successful manufacturers was Thomas Minton and Sons, founded by Thomas Minton in 1793. The popularity of the firm’s Chinoiserie ‘Willow Pattern’ tableware in the early 19th century allowed the company the freedom to experiment with products for new markets; smooth statuary porcelain ‘Parian’, ware ‘majolica’ glazed wall tiles and ‘encaustic’ tiles.

The process of manufacturing encaustic tiles was rediscovered by Samuel Wright, who obtained a patent in 1830 for the iron frames in which the tile mould was placed. A fly-press was used to press the clay into the mould to an even degree, to ensure greater consistency in firing and final performance. The combined designing and manufacturing prowess of the architect Augustus Pugin, and of Thomas Minton’s son, Herbert Minton realised the full potential of Wright’s invention. Encaustic tiles made a major contribution to the development of the Gothic Revival in architecture in the 19th century, a compelling juxtaposition of Victorian antiquarianism with the very latest manufacturing technology.

Encaustic tiles are ceramic tiles in which the surface pattern is not applied to the surface, but rather pressed into the tile using a plaster mould, and the sunken relief then filled with one or more different coloured slips. For complex tiles with several different colour clays, inclusion of stiffer coloured clays in the pressing can be required. The tiles are then fired at particular temperatures and conditions so that the base material and slips are bonded, and the clays partially ‘vitrify’ and become waterproof.

Medieval encaustic tiles were usually made of red clay, inlaid with a yellow design, and often displayed a naturalistic subject matter. 19th-century tiles were more colourful, and frequently included blue, green and white inlays. While naturalistic subject matter was common, the 19th-century tiles also had geometric and heraldic designs. Technically too, the 19th-century tiles were more accomplished. Advances in kiln technology allowed production, on a much larger scale, of a product that was dimensionally stable and without significant variation in colour and durability.

While many encaustic tile floors of the mid and late 19th century survive, few of them are as significant as those in the Palace of Westminster in terms of technology, design and craftsmanship. The Old Palace of Westminster was largely destroyed by fire in 1834 (Westminster Hall, the Chapel of St Mary Undercroft and the 16th-century Tudor Cloister being the only parts to survive). The New Palace was built after 1840, following an architectural competition, to designs by Charles Barry who was assisted by A. W. N. Pugin. The brief for the competition called for a design in the Gothic (or Elizabethan) style. Pugin was instrumental in bringing Herbert Minton the commission for the floors of Barry’s new Palace. The quality and scale of the floors was unprecedented and they are therefore of great significance in the history of Victorian interiors.

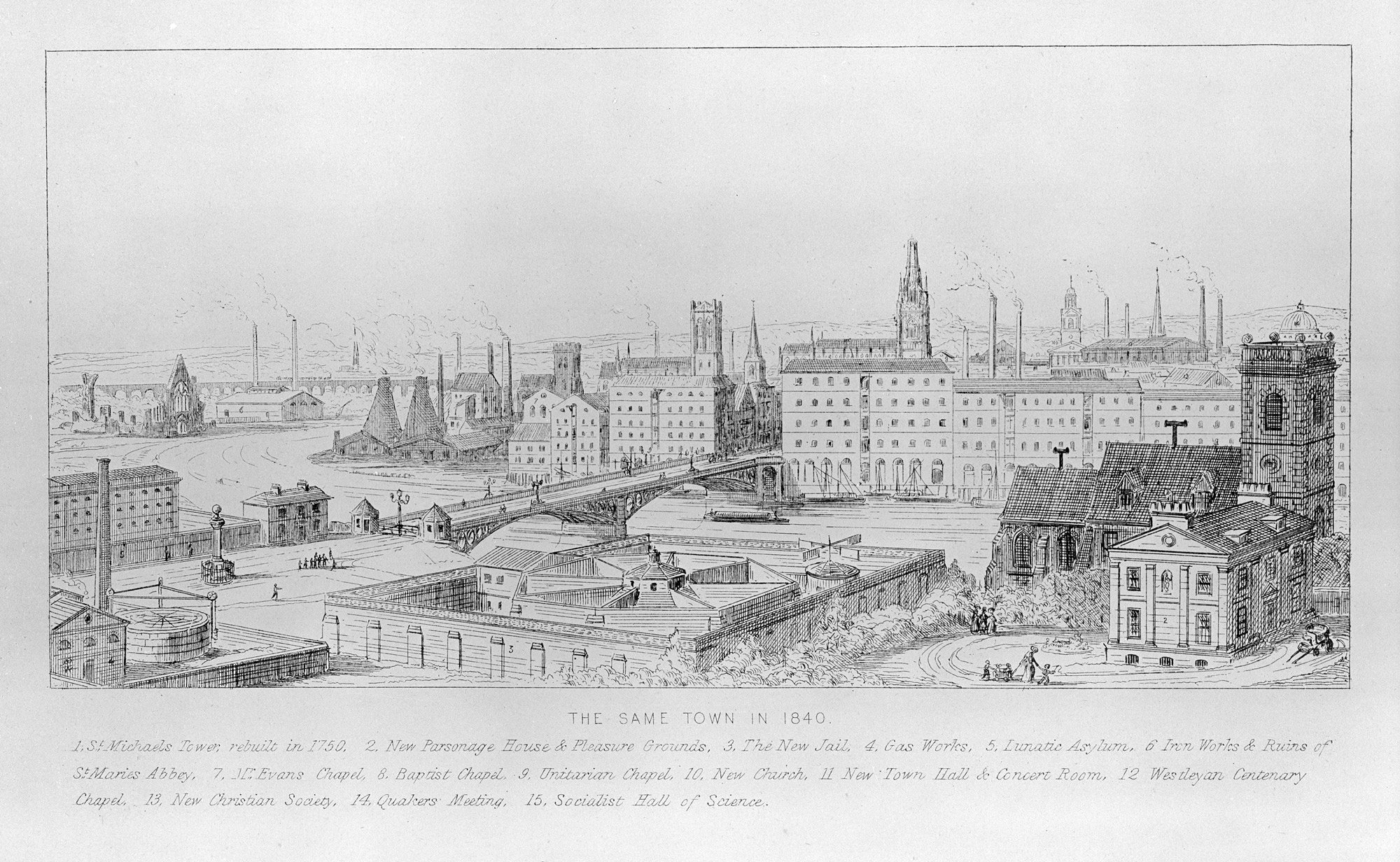

In 1836, Pugin published Contrasts (illustrated above), which featured paired engravings of idealised scenes from an imaginary medieval town compared with a dystopian industrial landscape that was not unlike that of the 19th-century Potteries. A Catholic convert, Pugin was not only a designer but a public advocate of Gothic architecture as a means to solve the many social problems of filthy Victorian industrial towns. The paradox of looking to the past to solve the problems of the modern era was expressed at the Palace of Westminster. While ostensibly backward-looking in its medieval architectural style, the Palace was at the forefront of Victorian design and engineering in terms of construction methods, fire-proofing, building services, and other technologies.

With the acquisition of the Minton archive by Stoke-on-Trent Museums, the history of Pugin’s collaboration with Minton is now better understood. Pugin typically supplied a drawing for a tile and then trusted Minton to complete the detail satisfactorily. In January 1852, Pugin wrote to Minton: ‘I declare your St. Stephen’s tiles are the finest done in the tile way; vastly superior to any ancient work; in fact, they are the best tiles in the world, and I think my patterns and your workmanship go ahead of anything’. .

The New Houses of Parliament, as Barry’s building was at first known, proved a prestigious global showroom for Minton; from the late 1850s, international orders for decorative encaustic floor tiles came from Australia (including Parliament House, Melbourne), Canada, the Caribbean, India (including the Royal Alfred Sailor’s Home in Mumbai), New Zealand and the USA (including flooring for extensions to the Capitol building in Washington). In Britain, the expansion of towns and cities in the 19th century also provided opportunities for new polychromatic decorative surfaces, from vast municipal complexes such as Rochdale Town Hall, to hallways in suburban villas. In the 20th century, however, encaustic tiles once again fell out of fashion. Mintons ceased to make encaustic tiles in the early 1960s.

The liquid clay ‘slip’ being poured into the

new encaustic tile.

Photo © Adam Watrobski/UK Parliament.

Modern Making

For the last 10 years, Donald Insall Associates has worked with Parliamentary Strategic Estates, tile manufacturer Craven Dunnill Jackfield, and works contractor DBR (London) Ltd to repair the Palace of Westminster’s encaustic tile floors. From 2006, the Parliamentary Estates Directorate commissioned and developed the process of making a one-inch-thick tile, rather the half-inch usually employed for modern work. From 2009, Donald Insall Associates was appointed to the project.

A major challenge at the outset was to develop a tile product in the exact facsimile of the historic tiles. Craven Dunnill Jackfield Ltd is the successor to Craven Dunnill & Co, which was formed by Henry Powell Dunnill during 1872. The company’s encaustic tile factory occupies the old ‘Jackfield Works’ building at Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire ‒ a building in the Gothic-industrial style which opened in 1874.

In a process that echoed Minton’s early painstaking experiments, a wide range of different clay bodies, slips, pressing methods, drying times and firing techniques were trialled to ensure that the new tiles had visual and physical properties as close to those of Minton’s original tiles as possible. Selected samples were then laboratory tested to confirm the slip resistance and surface porosity; accelerated abrasion testing was also undertaken to ensure that, in time, the tiles will wear in a similar manner to the existing examples. Progress in ceramic techniques has meant the loss of tiles during manufacture has been largely eliminated.

The project commenced on site during 2012 with work to St Stephen’s Hall. New tiles have now been installed throughout the majority of the Palace, with the project due to complete in autumn 2019. The major technical challenge of the central circular panel in the Central Lobby with its complex interlocking circular, curved, and concave triangle-shaped tiles inlaid with multiple colour slips is still undergoing final technical development. Elsewhere in the Palace, several years after the laying of the initial areas, the floors once again appear as Pugin and Minton intended.

Vitrified blues and whites catch the light. The mastery of decorative pattern is appreciable, in each richly-coloured tile and also in the complex arrangements of tiles over large areas. Ignoring the weathering of age, the new tiles are practically indistinguishable from Minton’s originals. However, there is one major difference. Mintons’ tiles emerged from the polluted and hazardous environment of the 19th-century Potteries. The area was, like much of 19th-century industrialised Britain, renowned for injuries at work, respiratory disease, and premature mortality. The new tiles, by contrast, are made in clean and controlled conditions in a rejuvenated late-Victorian factory, set within the leafy surroundings of the Ironbridge Gorge World Heritage Site. In the spirit of the Gothic Revival, the past has been rejuvenated using the latest manufacturing technology and standards. Of this, Pugin would undoubtedly have approved.