On Architecture and Memory

- | Hannah Parham

Memory has become something of a buzzword. It was the theme of this year’s London Festival of Architecture and the winners of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings’ Philip Webb Award for 2016 presented their work at an event entitled ‘Place and Memory’. It is no longer just conservation architects who delight in evidence of a building’s historical use and adaptation. When the glossiest of modern architects and the SPAB begin speaking the same language, something must be afoot. But for Donald Insall Associates the art of repairing, restoring or designing anew, while conserving the intangible qualities of historic places, has been at the heart of our philosophy for decades.

Philosophies of Conservation

An appreciation of the way in which buildings convey memory was at the root of the conservation movement in the 19th century. For John Ruskin, memory was one of the Seven Lamps of Architecture. In this architectural treatise of 1849, a chapter was dedicated to ‘The Lamp of Memory’ and in it Ruskin set out the philosophical justification for preserving historic buildings:

It is … no question of expediency or feeling whether we shall preserve the buildings of past times or not. We have no right whatever to touch them. They are not ours. They belong partly to those who built them, and partly to all the generations of mankind who are to follow us. The dead have still their right in them: that which they laboured for … we have no right to obliterate. What we have ourselves built, we are at liberty to throw down; but what other men gave their strength and wealth and life to accomplish, their right over does not pass away with their death; still less is the right to the use of what they have left vested in us only. It belongs to all their successors.

William Morris, founder of SPAB

© Alamy

The SPAB Manifesto, drafted by William Morris in 1877, developed Ruskin’s ideas into a set of conservation principles, encouraging regular maintenance and careful repair but eschewing the restoration or adaptation of historic buildings to meet changing needs. Architects, he urged, should romance the ruin and preserve each successive layer of history, up until around the 18th century. The approach has saved countless medieval churches, cathedrals and secular buildings from insensitive alteration. Yet Morris could not have envisaged the great numbers of buildings now listed or protected through conservation area designation when he formulated his principles. It is interesting to muse on what he might have made of the regeneration of Covent Garden when the flower market closed, or the post-fire restorations of Uppark or of Windsor Castle, or the adaptation of St Pancras Station for the arrival of Eurostar. He would certainly have baulked at listing the works of George Gilbert Scott. His dislike of Scott notwithstanding, the Manifesto was catholic in its celebration of ‘anything which can be looked on as artistic, picturesque, historical, antique, or substantial’. In this Morris was strikingly prescient and the definition of what constitutes ‘heritage’ continues to grow ever wider.

With the expansion of what is protected, the degrees of preservation and of permissible change have become more refined. Morris’ exhortation to ‘raise another building rather than alter or enlarge the old one’ cannot always be answered, especially in a world of diminishing natural resources. Conservation practices have developed in response to these challenges, and through the Venice Charter of 1964 and the Burra Charter of 2007, which present an increasingly systematic approach to ‘managing change’ and have introduced internationally-recognised standards of conservation.

That Every Place May Be ‘Truly More Itself’

Donald Insall Associates, founded in 1958, has been at the forefront of building conservation for nearly sixty years and our work encompasses many of these subtly different sets of principles. To maintain our pre-eminence in the field, the practice has recently held a series of debates and seminars exploring our practice philosophy from the perspective of a new generation of conservation architects and advisers. What has emerged most powerfully is that all our projects are underpinned by the governing motivation that, through our work, every place may be ‘truly more itself’.

This year, Donald Insall Associates was pleased to be one of six shortlisted teams in the National Trust’s International Design Competition for Clandon Park in Surrey. This Palladian mansion, built to designs by Giacomo Leoni from 1730, was devastated by a fire in 2015 resulting in substantial damage to its interior including the Marble Hall. Our entry – which has been devised in partnership with New York-based practice Diller Scofidio + Renfro – proposes the restoration of its principal historic rooms, combined with contemporary interventions into the more damaged areas of lesser interest on the upper floors. The fire, caused by a faulty electrical distribution board, showed that the notion that anything can be ‘preserved in aspic’ – as the conservation movement is often mischaracterised as desiring – is near impossible to achieve in practice; stuff happens, history never stands still. I believe our approach at Clandon, if we are successful, would illustrate the ways in which careful conservation and dynamic new design are not opposites, but can be part of the same creative process. This fits perfectly within the Palladian ideal of matching the genius of the ancients with the best that modern design has to offer.

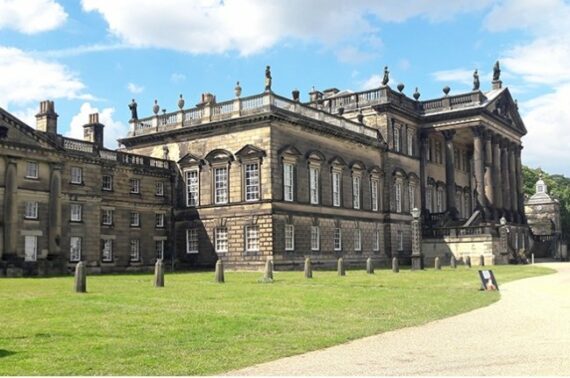

The practice will have the opportunity to put these ideas in to practice very soon at Wentworth Woodhouse in South Yorkshire. The team was the successful bidder in an open competition to lead a rescue operation to mend the roof of this extraordinary house. The grounds of Wentworth Woodhouse became an open-cast mine during the coal shortage of 1947 (‘like holding the Battle of the Somme in front of the Chateau of Versailles’, according to Marcus Binney) and subsidence and neglect have taken their toll. The house is now owned by a preservation trust and the Chancellor of the Exchequer announced a grant of £7.6m for the project in last year’s Autumn Statement.

Country houses are a fundamental part of our collective memory. The fire damaged Marble Hall, Clandon Park. Photo © National Trust / James Dobson

Review 2017

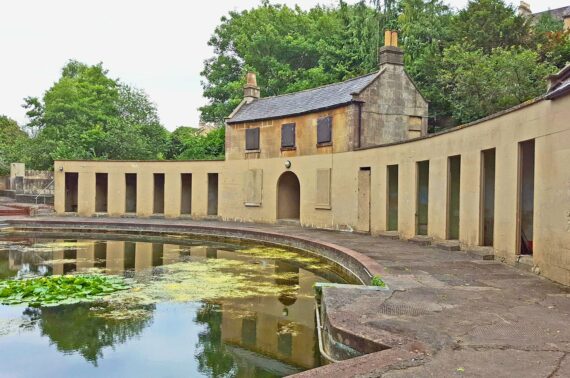

The articles presented in this Review explore the theme of architecture and memory in light of the places in which the Practice has worked this year. In some projects, memories of the past were harnessed to build support for repair and renewal. At Brodsworth Hall, for example, the complaints of former servants about the malfunctioning roller shutters in this Yorkshire country house, recorded in an oral history project, resonated with today’s English Heritage staff. This led, writes Simon Revill, to the idea of repairing and preserving two of the original patented designs as a record while providing an updated mechanism for the majority of the rollers. David Barnes’s article describes how a Heritage Lottery Fund project to rejuvenate a natural bathing pool in Bath is drawing on swimmers’ recollections of happy summer days to make the case for reopening; Cleveland Pools was in continuous use from 1815 until 1984. A new water-source heat pump promises a more comfortable, if slightly less authentic, experience.

In other places, memories of a building in its heyday are long-lost and the physical fabric is now the most powerful connector between past and present. No. 20 St James’s Square in London, says Helen Ensor, is a townhouse designed by Robert Adam in 1770 in a remarkable state of preservation. Fresh from examining the ruins of classical Italy on his Grand Tour, the young man who commissioned it clearly understood the capacity of architecture to speak to posterity. In the 1930s, the artist Rex Whistler deployed the power of painting to the same end, capturing the owners of Plas Newydd in Anglesey in an extraordinary set of trompe l’oeil murals in the principal rooms of the house. This very personal testimony, described by Matt Osmont, has now become part of our collective memory of life in a country house. Whistler’s story is said to have inspired Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, a major influence on modern perceptions of pre-War life in an English country house, and Plas Newydd is now open to the public by the National Trust. In an article about Chesterton Mill in Cambridge Karen Teideman-Barrett explores how technological changes over time are recorded in the surviving fabric, and how that will serve as a catalyst for regeneration.

Other historic places were designed as memorials from the start, as is the case at London Road Cemetery in Coventry, which contains the national monument to Joseph Paxton and is the subject of Christopher Thomas’s contribution. Aimée Felton suggests that some buildings hold memories of their past, embedded in the fabric. At the Temperate House in Kew Gardens the life of the rare plants housed in the building since the 1860s is imprinted in every joint opened by root systems, in remnant plant hooks and in exhausted soil. The practice has been working at Kew for over twenty years now and 2017 sees the unveiling of the restored Temperate House, the largest Victorian glasshouse in the world. Finally, Tony Barton reflects on our own institutional memory at Donald Insall Associates as we join the celebration of 50 years of conservation areas, a piece of legislation that reflects many of the principles established by Donald Insall’s pioneering work in Chester in the 1960s.

A watercolour of Wentworth Woodhouse by Sir Donald Insall

History Matters

Donald Insall Associates is uniquely placed to work on buildings with complex layers of history and meaning. We are one of the few architectural practices listed in the AJ100 to employ a dedicated team of historians and researchers who investigate the history of buildings, often making new discoveries, and see understanding the past as an inspiration for new design. The work of our architects follows the same principle and, in addition, their technological expertise can ensure the fragile qualities of historic places are conserved. Architects at Donald Insall Associates use their expertise to guide modern interventions that communicate our values and those of our clients to posterity, and ensure that historic buildings function effectively. Thus, active uses are sustained and a new generation is able to make its own memories, adding further layers of significance to a historic place. Through the conservation of historic buildings, the practice is privileged to participate in a continuous dialogue between past, present and future. By discovering the projects presented here in this Review, I invite you to listen in.