The Craft of the Glassmaker- From Alton Towers to Temperate House

- | Jeremy Trotter

From a domestic skylight to the great stained glass windows of medieval cathedrals, glass is a material that has wide universality. It provides a view to the outside and allows light to enter, yet it also protects the inhabitant from the weather. When combined with colour, it can offer visual delight.

Contemporary expectations are for glass to be invisible: a ‘non-material’ which eliminates the boundary between inside and out, while maintaining internal environmental conditions. Defects are to be excluded. This is achieved using scientifically-advanced manufacturing techniques that allow glass to be perfectly flat, free of flaws, and able to resist the strongest effects of UV light. The ubiquitous example of this are the vast expanses of glass fixed to the towers of the world’s cities.

The cultural and technological context at the time of its manufacturing is inherent in the properties of glass. Whereas the design and shape of the clay brick have stayed relatively static throughout history, the development of glass as a material has evolved in parallel with technological progress. In the earliest period of glassmaking, glass was a product of the craftsperson.

The conservatory at Alton Towers, repaired by Donald Insall Associates in 1982

The craft of glass

Just as a brick is of a size which means that it can be held in the human hand, under the crown process of glass manufacturing in the 18th century, the size of a glass pane was limited by the tools available and the abilities of the glassmaker. In what was a slow and labour-intensive process, the glassmaker would spin a molten bulb of glass into a flattened disc, from which a small pane would be cut. This typically limited the pane size to 16 by 10 inches. Glass was therefore an expensive material, and unsurprisingly its use was limited to small windows characterised by heavy timber glazing bars that were required to support the panes. Glassmaking was an arduous manual process, but it was a craft in which the glassmaker was fully immersed. The glass was not perfect; it had bubbles, distortions, and an uneven texture. These defects, however, ensured that the piece of glass was unique, and had a character of its own.

The crown process was swiftly usurped as technological advancements allowed for both pane size and quality to increase. The cylinder process had been in use in Europe since the 13th century, but it was Robert Chance of Chance Brothers glassmakers in Birmingham who improved the manufacturing process in the early 19th century. The company’s technological innovations allowed for larger panes to be produced both in greater quantities, and at a consistent quality. Concurrent with this were improvements in ironwork, which allowed for larger openings free of structural support.

The Chance Brothers were also pioneers of the plate glass technique, which can be seen as the precursor to modern float glass. One particular application of plate glass was at Windsor Castle, where the panes date from the 1840s and are set into large timber sash frames. Following the extensive fire in 1992, Donald Insall Associates carried out meticulous repairs to those windows that were damaged.

At Kew Palace, we took a similarly sensitive approach to repairs. Since 2014, the fanlights and sash windows have been carefully repaired in situ. Remarkably, we managed to replace decayed timber sections with new timber without having to remove the existing fragile glass.

Industrial Revolution

The rapid industrialisation of Europe during the Industrial Revolution saw steam power, mechanisation, and the standardisation of building components take hold as a philosophy of the construction industry. Refinements in production processes ensured that glass could be produced more cheaply, faster, and to more consistent tolerances than ever before. Glass was embraced as an essential building material. The Victorians were quick to seize upon the benefits of glass construction, employing it in large botanical glasshouses. Significant examples include the Temperate House at Kew (1862, Decimus Burton), and the conservatory at Alton Towers (1814, Robert Abrahams), for which Donald Insall Associates won a Civic Trust Award in 1982. Comprising seven domes, the conservatory was rescued from total dereliction and completely re-glazed.

A similar approach to repairs was taken at Temperate House, which re-opened after a five-year refurbishment project in 2018. The original glass panes had a green tint, which was thought to protect the living collection of plants from UV light. In 1879, a severe hailstorm shattered almost 39,000 panes of original glass, and the tinted glass was replaced. The replacement glass was lost again during WWII. Therefore, at the outset of this most recent refurbishment project, the building retained no original glass. The project sought to replace the existing glass in the same style, with curved bottom edges and a one-inch overlap to minimise water wicking. One change made to the glass specification was the addition of toughened glass adjacent to publicly accessible areas, to meet modern statutory regulations.

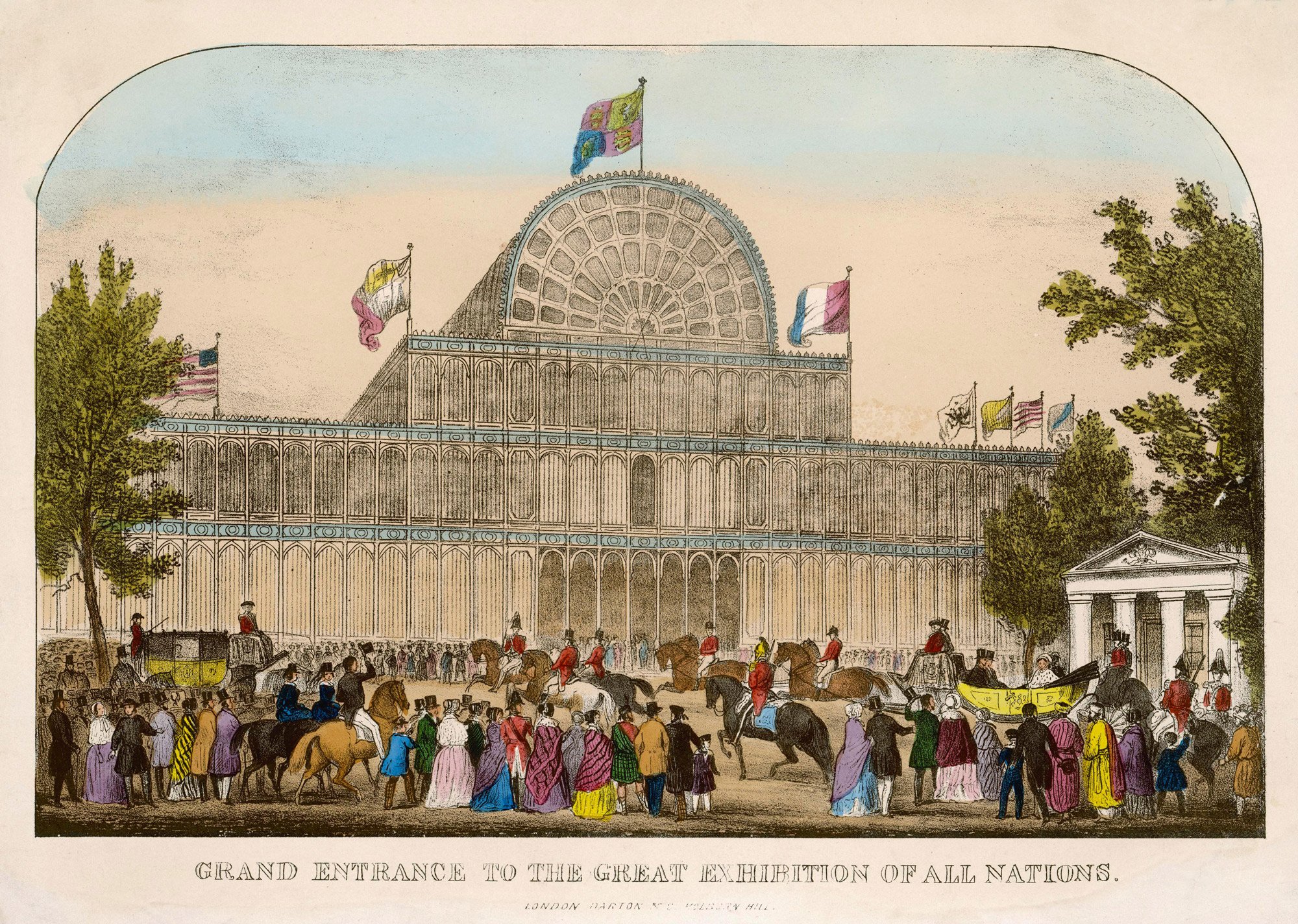

One of the most significant uses of glass in a public building was in 1851, when Joseph Paxton appropriated the engineering principles behind botanical glasshouses in his design of the Great Exhibition Hall in Hyde Park. Paxton’s design ‒ subsequently dubbed the Crystal Palace ‒ was the first public building that employed glass as the primary building material, and its design and construction embodied the philosophy of the Industrial Revolution. Paxton pioneered the use of standardised components that were fabricated off-site in workshops and foundries, and transported to London via the burgeoning railway network. All components were mass produced, using technologically-advanced production methods that ensured rapid fabrication at a low cost and consistent quality.

The Crystal Palace was of a modular construction, from the glass panes to the structural iron members. The Chance Brothers supplied almost 300,000 panes of glass ‒ a third of the country’s output at the time. Loaded onto trains in Birmingham, the panes were swiftly transported to Euston, for eventual delivery to Hyde Park. The fulfilment of this order was only possible because of the advanced manufacturing methods that were available at the time. Because the Crystal Palace had been assembled with screws and bolts in a modular manner, it could be rapidly dismantled when the Exhibition closed. All components were reclaimed, arguably making the Crystal Palace one of the first truly sustainable buildings. Still functioning as a private company today, the Chance Brothers supplied glass for our work at the Temperate House and the Palace of Westminster.

Glass works

From the latter half of the 19th century, the cylinder glass process gave way to the hand-drawn glass process, which in turn was superseded in the 20th century by the float glass technique. Every successive process reduced defects in the panes, and increased production speed and efficiency. Modern glass lacks visual imperfections and is a manifestation of modern technological achievements.

It is important to recognise the importance of rare survivals of historic glass and the craft of the glassmaker that these embody, as well as the potential for new glass to improve the performance of historic buildings and to make them work for modern life.

At the Horniman Museum and Gardens, Insall repaired the Coombe Cliff Conservatory. This was built in 1894, dismantled in 1981, and subsequently re-built on the current Horniman Museum site in the same decade. The Conservatory fortunately retained most of its original features, such as the roof which is formed of glazed fish scales. In 2016, Insall undertook essential repairs to the structure, providing new heating and a ‘Victoriana’-style tiled floor. This provided the Museum with a secure all-seasons venue for private hire and functions.

All materials age with time. The surface of the material might develop a patina, or it may suffer more severe corrosion, decay, cracking, or fissures. These defects imbue character into the material; the defects are a visual expression that time has passed. Glass, however, appears to be relatively resistant to gradual decay. Usually the timber glazing bar or the putty deteriorates first, leaving the glass pane intact but in a vulnerable state. Although it is a hard material, it is also delicate; the slightest impact can cause a crack that weakens the whole pane, or more likely lead to instant destruction. Other materials can withstand damage and retain at least some semblance of their original form. Glass, however, is fragile, and susceptible to shattering beyond repair in a way that other materials are not. Historic glass is a rarity, deeply imbued with character as much as a worn stone step or a bowed timber rafter; as such, it is a material that must be protected and celebrated.