The End of the Pier? Not for Colwyn Bay

- | Elgan Jones

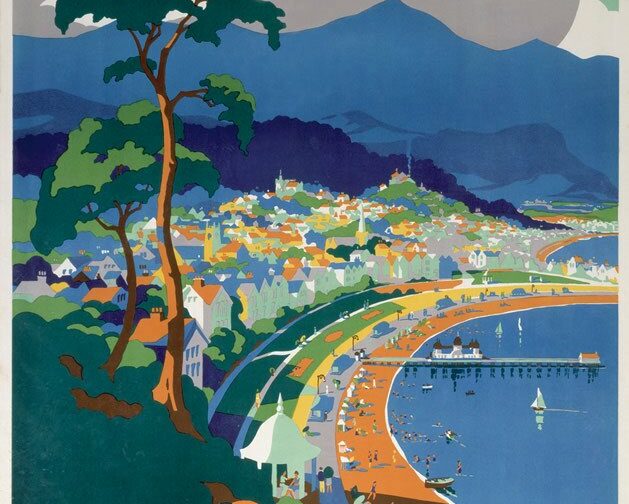

Seaside piers around the coast of Britain stand as a powerful reminder of the achievements of Victorian engineering. And there is no more eloquent symbol of the collapse of that prowess, and of the tourist economy which underpinned it, than the many disused or ruined piers which now mark several coastal towns. The 19th-century railway network, coupled with paid time-off for holidays for workers, turned many a seaside hamlet into a popular holiday destination. Colwyn Bay, in North Wales is one such example, its pier standing as a landmark of this dramatic social change. However, like many seaside towns, Colwyn Bay faced steep decline during the latter half of the 20th century. A lack of investment and changes in ownership resulted in the collapse of large portions of Victoria Pier during a storm in 2017, with the remainder of the structure left on the brink of falling down.

The original pier, opened in June 1890 was just 96m long, comprising a timber promenade deck, fine cast-iron balustrading and a remarkably elaborate 2,500 seat pavilion in the Moorish Revival style. In 1903, the pier was extend to a length of 227m and in 1916 a smaller lightweight canvas structure in the form of the Bijou theatre was erected at its furthest extremity. In 1922, the pier suffered its first of three devastating fires which destroyed the main pavilion building. Within a year, a replacement had been redesigned, constructed and opened but this was to have an even shorter lifespan, catching ablaze in 1933. Later the same year a fire also destroyed the Bijou theatre. This unfortunate series of events led to questions over the wisdom of building venues for public entertainment on the end of a pier in the Irish Sea, yet the Council remained undeterred and within a year of the fire a third pavilion had been redesigned, constructed and opened. The will and speediness to rebuild the pier and pavilion demonstrated the important role the pier played in the town’s economy at that time.

The third and final pavilion to be built on the pier was designed by Professor Stanley Adshead in an Art Deco style. Unsurprisingly, it was a fire-resistant design resulting in a lightweight steel frame lined in asbestos. Adshead collaborated with his daughter, the artist Mary Adshead, and Eric Ravilious, the prominent painter and watercolorist; murals by both decorated the internal walls. Luckily the Adshead and Ravilious murals were saved and removed from the building prior to its dismantling, following the collapse in 2017.

After the 2017 disaster, many options were considered including demolition; the retention of only the cast-iron columns as a form of sculptural memory; partial; and full restoration. Consent was granted to dismantle the remaining part of the pier before then reinstating only its first three bays. Insall is charged with meeting the practical challenges of repairing, designing and restoring the pier, with only nine standing columns and the stone sea wall still remaining.

Establishing a philosophy

We inherited a design with a confused conservation approach, including new elements expressed in both traditional and contemporary styles, and historic fabric being reused in an inauthentic manner. From the offset we were keen to establish a clear and consistent philosophy of repair which would protect the legibility, integrity and character of the pier. Any repair, intervention or specification would be based on understanding the historic fabric, the setting and its significance. New interventions would be expressed in a contemporary but sympathetic manner. We then worked alongside the conservation officer on design and details, to better align with this approach.

Environmental conditions presented a key challenge in the design process: the pier’s exposure to soluble salts and repeated wetting and drying bring an ongoing risk of accelerated weathering of decorative coats and corroding metalwork. Our approach was underpinned by an understanding of the pier’s original construction and later adaption and, critically, any details which had contributed to its deterioration. In these instances, we considered opportunities for correcting any inherent design defects to achieve greater longevity and reduce the maintenance requirements without adversely affecting significance.

A common failure observed along the perimeter of the pier was the fixing of the cast iron balustrade to the timber sole plate beneath, a detail which relied on the paint system to protect the timber from decay. Once the paint system failed, it allowed moisture into the timber, causing the balustrade to become unstable. To address this we redesigned the detail to introduce a metal stub beneath each of the balustrade posts, these in turn fixed to the metal structure thus eliminated the reliance on the timber’s integrity. With a new timber sole plate, matching the original profile and notched around the upstands, the overall appearance of the detail remained as original.

This informed, technical approach meant that more of the original design could be preserved. Earlier proposals for the pier had altered the position of the balustrade, aligning it with the columns below. We proposed reinstating the original arrangement, where the cast iron balustrade projects outwards over the sea; as well as being more historically accurate, this will give the pier a generous sense of breadth and maintain a clear definition between the delicate cast iron balustrade and the heavy, more utilitarian structure below.

At Victoria Pier the ironwork has always been painted to reduce corrosion and provide a decorative finish. The method of cleaning and repairing the corroded ironwork would result in the loss of the built up of historic decorative layers and therefore it was vital that analysis was undertaken prior to the evidence being lost. We undertook paint analysis to record these historical changes and to inform the new decorative scheme. This found the earliest sample to date to the period of reconstruction in c.1934, painted in a polychromatic fashion in pastel shades of salmon pink and cream. These bore a striking resemblance to those used in Adshead and Ravilous’s murals and the interiors of the Art Deco pavilion.

Despite Colwyn Bay pier’s turbulent history, the fact that there has been a continued commitment to secure the future of its fine pier is testament to its centrality in the regeneration of the town and the waterfront. Our role in the project has brought a considered conservation approach, conserving what is significant about the pier whilst allowing lessons learnt from its previous disasters to inform new elements, which will better preserve the fabric in the long-term.