The Library Renewed

- | Helen Warren

The colleges of Oxford and Cambridge occupy a unique place in the heritage of the nation. Despite originally being places of religious scholarship, they avoided the fate of abbeys and convents, which were destroyed during Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. Remarkably, these scholarly communities survive today with sites and buildings which continue to be used and occupied in much the same way as they were originally intended, as places of communal learning. This combination of historic architecture and the continuation of centuries-old collegiate traditions defines both cities.

However, ensuring that these historic buildings are protected whilst also remaining relevant to modern-day needs is a delicate balance. Our team of researchers, historic building advisors and conservation architects have been busy for the past two years, collaborating with Nex Architects on a building that lies at the heart of one of the colleges, in the historic core of Oxford: the Library at Exeter College, built in c. 1856-7 by the builders Symm & Co. of Oxford to designs by the architect George Gilbert Scott. The Rector (head) of the College, Professor Sir Rick Trainor, sums up the College’s aspirations for the building:

‘I am delighted that the College’s exciting plans for renewing its Library have met with such a positive response and can now go ahead. As a tremendously popular building at the heart of College life, it is essential that we preserve the historic fabric of the Library inside and out while making it fit for use in the 21st century and beyond. Exeter College’s Library has been a place of inspiration to so many of our students past and present, including Sir Philip Pullman and JRR Tolkein. Our vision is to provide a study space tailored for modern students and academics, whilst maintaining the Library’s inspirational atmosphere and exceptional beauty for generations to come.’

Insall has uncovered the narrative behind the site’s layered building fabric, studied its condition and considered its varied heritage values in order to guide the approach to its conservation and adaption.

Exeter College is Oxford’s fourth oldest college and has been situated on its central Turl Street site since 1315; its buildings have seen waves of renewal and adaption to suit changing fortunes, tastes and needs. The Library is no exception, having taken several different forms and occupying several different locations over the years, before settling between the Rector’s and Fellows’ Gardens, by 1857. To some, the multi-layered fabric enshrined in the College buildings holds the key to their value – that of reliable evidence.

‘There is no kind of historical evidence which is so precious, so certain, so incontrovertible as that supplied by ancient buildings.’ (Bryce, 1879)

Evidential value is concerned with what physical remains can tell us or confirm about historic construction methods, dates, rituals and practices, which we would otherwise not know. Examples of this at the Library have included the ability to determine the original decorative scheme through analysis of paint sample stratigraphy (by Hirst Conservation), and the analysis of stonework joints and details to decipher the original extent of the building and its circulation arrangements.

Historic value suggests that it is the associated past events and people behind a building which make it special. The Library’s historic value derives from its role in the development of the College, and in particular its mid-19th-century transformation. The University of Oxford and its colleges were undergoing profound changes in the early-mid Victorian period, rapidly expanding and modernising to meet the needs of a newly-industrialised and increasingly imperial society. Exeter was in the vanguard of reform, and this is manifested in the new buildings that the College erected in this period, largely rebuilding its mediaeval and early modern structures. The Library, along with the Chapel, Rector’s Lodgings and a series of undergraduate rooms, tells this story of transformation and renewal.

The Library’s historic significance is also reflected in its associations with Rectors, Fellows, post-graduates and undergraduates of the College, some of whom have a particularly strong link with the Library such as William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, whose beautiful stained glass roundels can be seen in some of the ground floor windows. The vision of JRR Tolkien sitting, reading the book on Finnish grammar that he found in the Library and supposedly helped to inspire the Middle-earth of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, is unavoidably conjured in the mind’s eye when walking amongst the bookshelves.

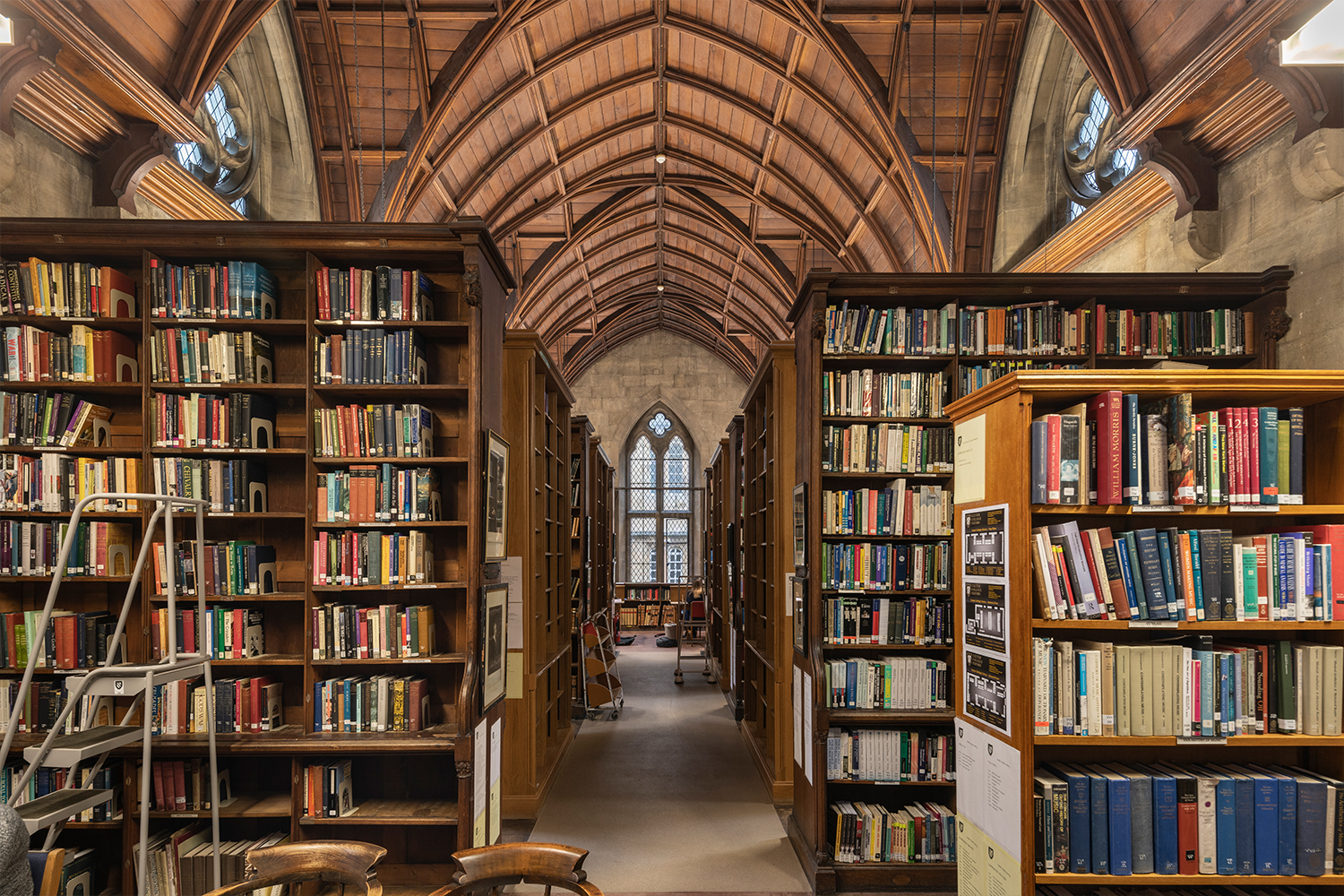

Others may value the building for its architecture. The Library forms a group with the other buildings designed by Gilbert Scott for the College. The Library is, to quote the forthcoming Pevsner volume ‘also [like the Chapel] in the late C13 style, but more personal in the handling’. Commentators, including biographer Gavin Stamp, have noted the power of the close arcading of the upper floor, which is largely blank but for four lancet windows; this was inspired by mediaeval traditions of library architecture. Other important features are the dormers with geometrical tracery and the timber-lined vaulted ceiling of the upper floor of the main range. The building is particularly special because of the high-quality materials, the skilled craftsmanship and level of detail displayed in its construction, from the carved stonework to the individually designed timber bookcases.

“The diversity of values illustrates the complex nature of conservation; what is of value to me may differ to what is value to you, and almost certainly what might be of value to future generations.”

But the value of historic buildings lies in much more than bricks and mortar. To many people, they provoke a deeper, more symbolic consciousness about time and mortality. We think of the people who have touched the same wall, walked up the same stairway or taken a book from one of the shelves and imagine what their life would have been like. The visible age of a building, elicited through patina on woodwork, faded paintwork or eroded stonework, is of value – a sentiment beautifully expressed by John Ruskin in 1890: ‘The greatest glory of a building… is in its age, and in that deep sense of voicefulness, of stern watching, of mysterious sympathy, nay even of approval or condemnation, which we feel in walls that have long been washed by the passing waves of humanity.’ Values such as the communal, cultural or spiritual cannot necessarily be associated with the building’s fabric, but are derived from patterns of behaviour and traditions. The continuous use of the Library by generations of scholars, fellows and staff contributes to its significance as strongly, if not more so, than any individual part of the building’s components.

The diversity of values illustrates the complex nature of conservation; what is of value to me may differ to what is value to you, and almost certainly what might be of value to future generations. How can the conserver and custodian please both the archaeologist’s thirst for evidence, the romantic’s desire for gradual deterioration, and the owners’ responsibility to ensure the building remains fit for purpose? To what extent can the need for authenticity be prioritised over and above the survival and traditional use of a building?

At Insall we recognise that change is often needed to ensure our historic buildings remain viable. Our approach is always to understand a building’s heritage values upfront and use this to guide the process, looking to minimise harmful intervention as much a possible by thinking creatively about how alterations could be sited, scaled and detailed, and looking for ways to preserve and enhance what is special about a building or place.

This approach at Exeter College Library has informed the recently approved scheme. The works include essential repairs and re-instatement of lost details (seen on historic photographs) such as missing pinnacles, carved heads and foliage to stonework and lions to rainwater pipes, to ensure that the Library’s architectural value can be enjoyed by future generations.

In order to make all floors of the building accessible a new lift and staircase have been carefully designed. Located in an area previously altered in the 1950s, the new lift shaft will sit discreetly behind an existing stair turret with the staircase nestled in a previously unoccupied gap between the neighboring Bodleian’s buttresses. The removal of the 1950s first floor which crudely bisects the annex, will allow the original, single volume and Gilbert Scott’s traceried windows to be appreciated at their full height once again. Where new additions have been required they have been designed by Nex as bespoke pieces of furniture intended to echo the craftsmanship of Gilbert Scott’s work, in an honest way. Services will be re-routed and hidden beneath the plinths of bookshelves, in significant upgrades to the building’s services (including those facilitating up-to-date information technology) and environmental comfort and performance.

The approved scheme, which is expected to be completed by Autumn 2023, ensures that the building remains relevant for today’s users without compromising its architectural quality, atmosphere and idiosyncratic charm.