The (Other) Baths of Bath

- | David Barnes

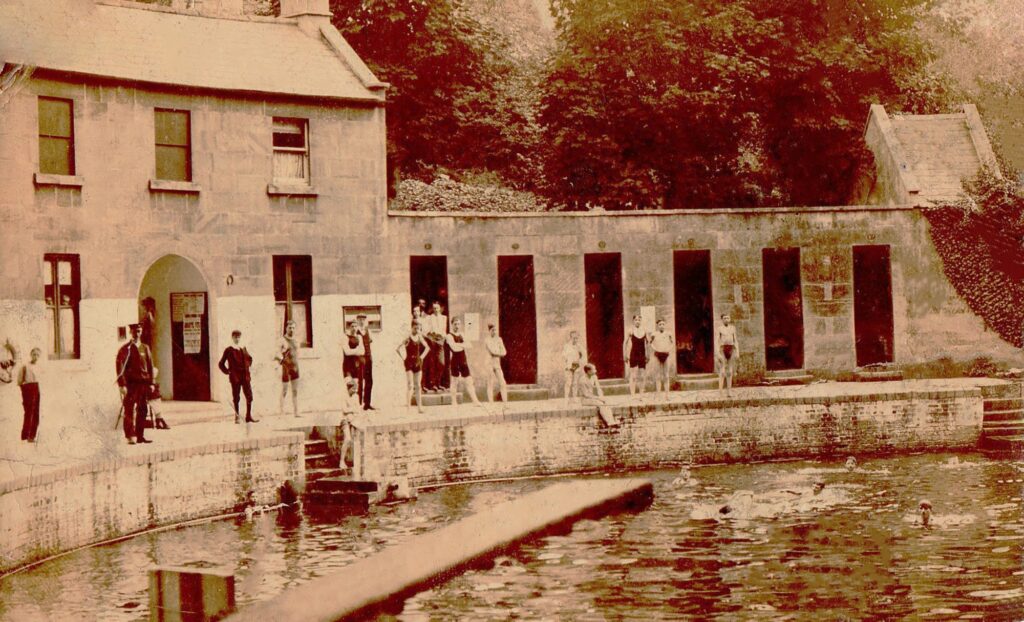

Georgian architecture and bathing are synonymous with Bath and the two come together in the unique and little-altered Cleveland Pools. Opened in 1815 as a discreet and civilised adaptation of the natural swimming facilities provided by the adjacent river Avon, the crescent-form development was contemporary with some of the final phases of the Georgian expansion of the city. The original arrangement included a river-fed main pool for male bathers, whose activities had been somewhat curtailed by the 1801 Bathwick Water Act which prohibited nude male swimming in the river. There was also a smaller, separate, spring-fed ladies pool, screened and enclosed by a high wall.

The Original Development

Cleveland Pools was constructed on the fringe of what is now the City of Bath World Heritage Site, alongside what was – at the time – an over-ambitious residential development to the north and east of the centre which included extensive pleasure gardens. The speculation failed because Bath’s economic and social status was in decline, as fashionable society moved away to new resorts. Just across the river from Cleveland Pools, Grosvenor Pleasure Ground, which opened in 1792 providing archery fields, bowling greens, a maze and rowing facilities, was never fully realised and had reverted to domestic gardens by 1820. The Pools also suffered fluctuating fortunes, but remained in largely continuous use until 1984. After a brief period as a trout farm, the Pools were abandoned in 2003.

Surprisingly, 200 years of alteration, extension and adaptation have not significantly diluted the modest architectural clarity of the original design. This has been popularly attributed to John Pinch the Elder, who was working on elements of the surrounding Bathwick Estate and was also among the original subscribers to the Pools.

A Suburban Backwater

The former vitality and social vibrancy of the Pools, however, has been replaced by peaceful decay and disuse; the prevailing atmosphere is closer to semi-rural with over-mature self-seeded trees screening the site from its neighbours and slowly encroaching on the remaining structures. Initially listed in 1975, Cleveland Pools was subsequently upgraded to II* in 2006, but remains on the Heritage at Risk Register. Following a Round 1 award from Heritage Lottery Fund, Donald Insall Associates was appointed in August 2015 by Cleveland Pools Trust to develop the proposals.

Cleveland Pools is tucked away behind terraced housing on a residential cul-de-sac and can only be reached via a small pedestrian gateway opening onto a steep and narrow pathway. The locality is now a suburban backwater bounded by the river, railway line and canal, and occupants of residential properties around the site have become accustomed to the quiet enjoyment of their neighbourhood.

The historical and architectural relevance of the Pools is still quite evident, but the redundant site now has a very different relationship with its immediate surroundings. Restoration of the Cleveland Pools as an open air swimming facility will rely on once again attracting large numbers of visitors to allow the sustainable re-use of the Pools as a viable, not-for-profit community pool.

“Come on in, the water’s lovely”

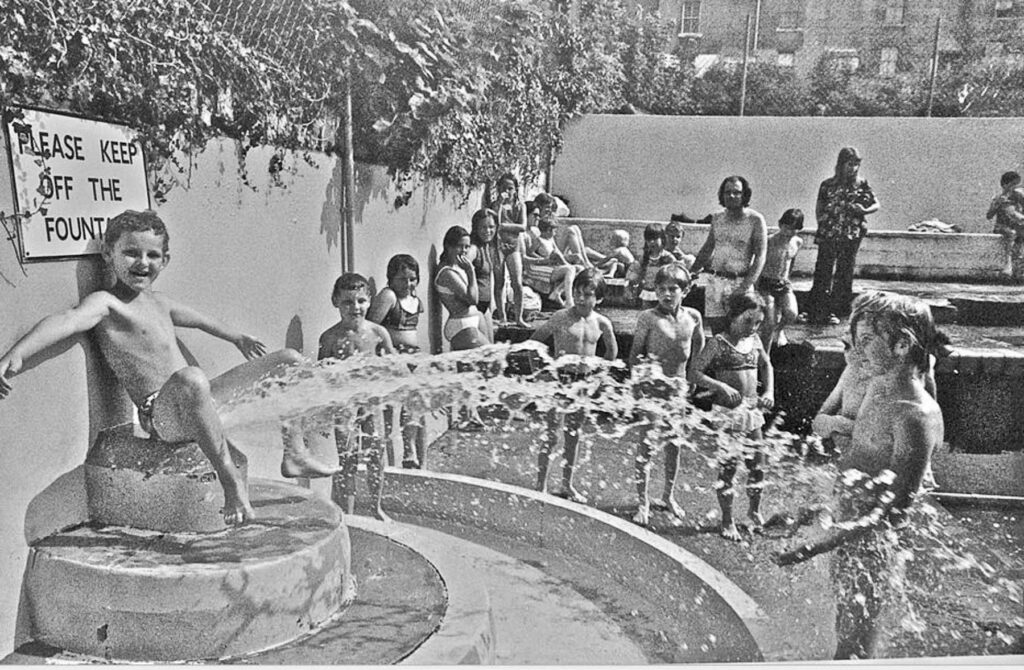

Local people have fond memories of swimming at Cleveland Pools during the 20th century, as evidenced by numerous comments submitted in support of the recent Planning and Listed Building Consent applications. Such recollections are vital in recording public enthusiasm for the project and re-establishing the broken chain of community use at the bathing pools.

Being an open air, unheated facility, the popularly of Cleveland Pools in the past would have been dictated by the seasons and vagaries of daily weather conditions. Consequently, it is not altogether surprising that people’s recollections are overwhelmingly positive, as they are most likely associated with fair weather. The current proposal is based on natural, bacteriological filtration of the pool water and will employ a water source heat pump to extract heat from the adjacent river to allow bathers to swim in much warmer water, hopefully widening the appeal.

However, whilst the success of the project relies upon encouraging visitors to discover this history and, even better, physically experience swimming in the oldest outdoor public pool in Britain, there are understandable concerns about the potential impact on the immediate neighbourhood. Very few of the existing nearby residents lived in the area when the Pools were last open, and there is some reluctance to accept the levels of seasonal activity associated with a community pool.

To reconcile these issues, it is tempting simply to consider the antiquity of the Pools against the transient nature of the occupancy of the surrounding housing, which is predominantly of a later construction date. We can readily establish the national significance of this virtually complete Georgian pool complex, with its direct connections to the Georgian architecture of Bath. The Pools tell us about the changing traditions of bathing in society and the development of Bath, but public understanding of this unique place is better served by its use for swimming than by any number of ‘heritage’ interpretation panels.

There is a rare opportunity to rescue, sensitively conserve and restore the original building to its original function. The updated facilities will provide a living and evolving history for this important heritage site that is inescapably part of Bath.

Planning and listed building consent have recently been granted for the restoration of Cleveland Pools and we look forward to future generations being able to experience and absorb many more happy memories.