Curating Catastrophe: The Enduring Legacy of Bombed Churches as War Memorials

- | Ben Clark

In 1945 the Architectural Press published a short booklet entitled Bombed Churches as War Memorials. Through vivid conceptual sketches by artist Barbara Jones and detailed designs by architects such as Hugh Casson, it argued that a handful of bomb-damaged churches across Britain should be preserved in a freshly ruined state, so that they might become ‘places of value and great emotional significance to future generations’. It came to pass that around 30 churches in England were memorialised in this way.

Today, such structures present conservation challenges which are no less complex than churches in active use. In Liverpool, Insall’s work on what is known locally as ‘The Bombed-Out Church’ responds to problems of decay, safety and presentation. Our approach aligns powerfully with that advocated in Bombed Churches as War Memorials.

The Allure of Ruined Churches

While ruins resulting from violence, accident, or natural disaster have been around for as long as there have been buildings, the idea that they could be utilised as memorials does not appear to have emerged until the Second World War.

The architectural profession was the first to suggest that new means of commemoration and memorials were required in response to the devastation of towns and cities and the creation of ruins on a vast scale. In 1943, The Architectural Review sought to tackle ‘two burning questions of the day: what would be the sincerest, most genuine memorials to the dead of this war, the dead overseas and on the home front, and what is to be the future of the bombed churches of Britain’. In 1944, The Times published a letter advocating that bomb-damaged churches be ‘preserved in their ruined condition, as permanent memorials of this war’, signed by a group of prominent cultural figures, including the director of the National Gallery, Sir Kenneth Clark.

Although the treatment of war ruins, as advocated by the likes of Casson and Clark, was novel, it was rooted in the Romantic English landscape tradition of the 18th and 19th centuries, which associated ruins with the natural decay, the passing of time, and the gentle melancholy of loss. ‘Bomb damage is in itself Picturesque’ claimed Kenneth Clark in the early 1940s.

It wasn’t the case that buildings could simply be left as found in 1945, however. In her 1953 Pleasure of Ruins study, Rose Macaulay wrote: ‘New ruins are for a time stark and bare, vegetationless and creatureless; blackened and torn, they smell of fire and mortality.’ Casson et al described the process of memorialisation:

Preservation is not wholly the archaeologist’s job: it involves an understanding of the ruin as a ruin, and its re-creation as a work of art in its own right…

Through the adoption of a revived Picturesque aesthetic and low-impact approach to conservation, Bombed Churches proposed a means of coming to terms with the catastrophe of war by transforming sites of tangible destruction into more familiar ruins of gradual decay.

This approach coincided with wider architectural debates concerning post-war reconstruction. Public authorities across Britain, prompted by architectural journals such as the Architectural Review, adopted a ‘new Picturesque’ aesthetic in their approach to the urban realm which combined popular modernism with English traditions. The majority of sketches included in Bombed Churches show the preserved ruins, generally of medieval Gothic or 19th century Gothic-Revival style, surrounded by modern commercial redevelopment.

Sketch perspective from the ruins of the old cathedral, Basil Spence, 1952 © Historic Environment Scotland.

Ruin Curation in Practice

At Coventry Cathedral, the ideas in Bombed Churches reached their apotheosis, gaining international attention. On November 14th 1940, the medieval St Michael’s Cathedral in Coventry was destroyed. Although the city’s warplane factories were the main targets, 554 civilians were killed the Cathedral was reduced to a burnt-out shell with only the outer walls, the tower and the spire remaining. It was the only cathedral in Britain to be destroyed during the war and Coventry was quickly identified nationally as representing the suffering of towns and cities across the country. Although the decision to rebuild the Cathedral had been taken the morning after the raid by the Provost Richard Howard, it was not until 1951 that Basil Spence won the architectural competition for a new cathedral. By this time, the reconstruction of the Cathedral had become an intensely political subject as a symbol of national regeneration and of international peace and reconciliation.

Central to Spence’s modernist design for the new Cathedral was the preservation of the ruins in their entirety as a ‘memorial to the courage of the people of Coventry’. Echoing the language of Bombed Churches, Spence wrote in his competition entry ‘Through the ordeal of bombing, Coventry was given a beautiful ruin’.

However, even before the competition for rebuilding the cathedral had been announced, the ruins of St Michael’s had been embraced by the local community. After the raid, the Cathedral ruins had continued to serve as a place of worship and annual commemorative services were subsequently held for the victims of the ‘Coventry Blitz’. In 1941, a local stonemason, Jock Forbes, created an altar from rubble found on the site (the ‘Altar of Rubble’) and erected it in what had once been the sanctuary. A Cross, fashioned from the Cathedral’s charred roof beams and bound together by blackened wire (the ‘Charred Cross’), was then placed on top of the makeshift altar. On VE Day, 8 May 1945, the people of Coventry flocked to the ruins to celebrate the end of the war. The rubble was finally cleared in 1947, and a temporary garden of remembrance created. A year later, Howard had ‘FATHER FORGIVE’ inscribed on the sanctuary wall behind the Altar of Rubble, a gesture towards the Cathedral’s commitment to peace and reconciliation.

Photograph of the new entrance to the ruins, cut from the remaining tracery of a former window, by Henk Snoek, 1962. Photo © Historic Environment Scotland.

The Bombed-Out Church

The preservation of St Luke’s Church in Liverpool – a conservation project for Insall – was driven by the local community rather than any official architectural intervention. Occupying a prominent position in the city centre, St Luke’s Church was built in 1811 under the supervision of local architect John Foster Snr, with the chancel added in 1822 by his son John Foster Jr. On the night of the 5 May 1941, the church was gutted by an incendiary bomb. No lives were lost, but the building blazed for three days.

The local community saved St Luke’s from demolition by the city corporation in the 1950s and adopted it as an unofficial war memorial to the civilian casualties sustained by Liverpool during the Second World War. The remains of the building were subsequently Grade II* listed in 1952 but the site remained vacant and unused.

St Luke’s typifies several prominent conservation challenges associated with ‘curated’ ruins, which a new generation of architects and urban planners now need to contend. The subsequent lack of protection from the elements caused by the preservation of the ruinous state of the building began to take a damaging toll on the structural integrity of the outside walls. In October 2015, Insall was commissioned as part of a joint-funded project by Historic England and Liverpool City Council to restore the structural integrity of the church ruins.

These works, which were completed in May 2017, involved removing destructive vegetation; dismantling and rebuilding the precariously crumbling top courses of the walls of the nave and chancel; rebuilding loose stone pinnacles and repointing those most damaged from the heat of the incendiary bomb; and repairing the west tower and vulnerable tracery windows. Replacement timber sections were introduced to support the weight of the historic bell frame and a replacement roof structure at the highest point of the building, with a traditional lead sheet covering to keep it low and out of view from ground level, was designed to provide further protection to the inside of the tower. The cracked mullions and remnants of stained glass were reinforced by the use of hidden steel pins. Where replacement carved stone was installed the detailing was crisp and the profile of the element true to the original form, in the matching stone, so that the new work would be visible distinguished from the original. New elements, such as the slate weathering to the top of the walls were specified to be clearly recognisable as a modern intervention but using traditional materials.

In many ways, the scheme mirrored the ideas first espoused back in the 1940s, blending traditional techniques with modern conservation and townscape principles to breathe new life into a site of destruction. Following the completion of the scheme, the future of St Luke’s was subsequently secured for the next 30 years by the appointment of an operator to run the site as an arts and events venue. The main tower is still standing and the roofless congregation space of the church, still enclosed by highly detailed tracery walls, is used for art exhibitions, concerts and other events. As such, the preserved fragments of the church are not only reminiscent of the building’s original function but also demonstrative of the post-war history of the site.

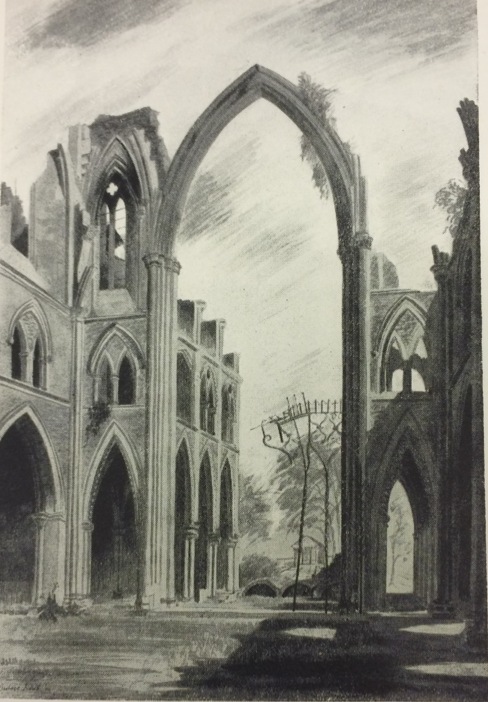

Barbara Jones, The conservation

ruins of St John’s London in Bombed

Churches as War Memorials.

Image © The Architectural Press.

Preserve, Commemorate, Use

Insall’s work at The Bombed-Out Church provides a chance to re-asses a number of key issues within the context of curating bomb-damaged buildings as war memorials. First and foremost, it is now acceptable for the symbolism accumulated through the destruction of a building to outweigh that of any potential historic and architectural significance that may have come before. Second, ruins created through political violence do not necessarily have a ‘natural’ lifecycle, and should be kept alive for as long as there is a will to collectively remember the events surrounding their destruction. Third, and perhaps most importantly, war ruins can function as a place of memory while also having value for a range of other social, political and economic interests and uses.