Historic Building Research: Unravelling the history of old buildings

- | Helen Ensor

Helen Ensor considers the art of historic buildings research and explains why it is often not straightforward.

Historic buildings are fascinating and they are all around us. As material evidence of the past they can be archaeological, providing insights into social history or evidence of political changes, and to the tastes and aspirations of interesting individual people. All historic buildings have undergone change in their lifetime – even those that appear to be authentic and ‘original’ are not the same as they were when they were first built, and understanding the physical changes which have taken place, and then deciding what elements of the remaining fabric are of significance, is one of our key tasks. At Donald Insall Associates, we are exceptionally good at unravelling and explaining the history and significance of old buildings and places, and all of our heritage planning and listed building consent advice is based on this robust, detailed and illuminating research. So how do we do it?

Secondary Sources

The term secondary source refers to things other people have written about a particular building or site. All of our research projects begin by collating the standard secondary sources, which might include reference to Pevsner’s Buildings of England, the Victoria County History, the Survey of London or British History Online, monographs on particular architects or thematic surveys of certain building types such as farm buildings or public houses. The list description is a secondary source but often contains references to primary sources (see below for more on that). Our particular knowledge and specialisms come into play here as there are a number of secondary sources which we use often which would not be generally known about – in Oxford, for example, I frequently turn to a book published in 1975 entitled Oxford Stone Restored which details the massive restoration campaign which was undertaken throughout Oxford between 1952 and 1974 and which saw the re-fronting and in some cases almost complete rebuilding of most historic buildings owned by the Colleges and University in central Oxford. Without this book, one would naturally assume that the stonework of, say, the Old Ashmolean (now the Museum of the History of Science) related to the primary phase of construction in 1679; with it, the extent of stone replacement and re-carving of architectural details which happened in 1954, and therefore the significance of the fabric itself, becomes clear.

Old Plans

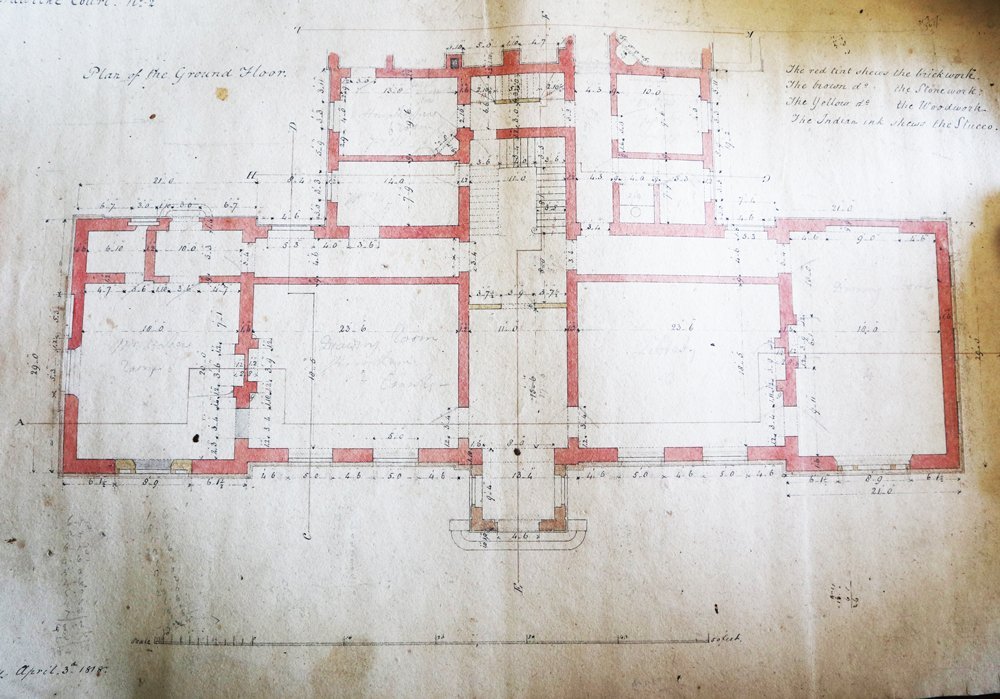

This is the simplest way of working out how a building may have changed over time. The existence of old plans, be they planning applications from the 1940s or 50s, drainage plans from the 1920s or 30s, or even the original architect’s drawings are one of the most helpful – and often elusive – pieces of evidence to find when researching old buildings. In London, well organised local archives and good record-keeping means that planning and drainage drawings are often to be found. The RIBA keeps many historic drawings and other museums and archives have the collections relating to specific, often nationally important, architects. When researching a country house in Gloucestershire, a colleague and I recently found the original plans for the house, drawn up in 1818, in a bin bag in a bathtub in a disused part of the house; whilst this was incredibly exciting it is also very rare!

1818 ground floor plan by Robert Smirke of a country house in Gloucestershire discovered in a bin bag in a disused part of the house

On another project in London, we found drainage plans from 1927 which showed a staircase having been installed to link the ground floor and basement in one of the main rooms. This had subsequently been removed and no trace could be seen on-site, but the client wanted to put in a new staircase in the same location and the discovery of these plans made it hard for the conservation officer to resist. Once found, the interpretation of old plans is critical, as often all is not as it seems. The plans may not accurately reflect the evidence on the ground – is this because there were errors in the draughtsmanship, or reflect alterations which were never made? Interpreting old plans wrongly is an easy mistake to make.

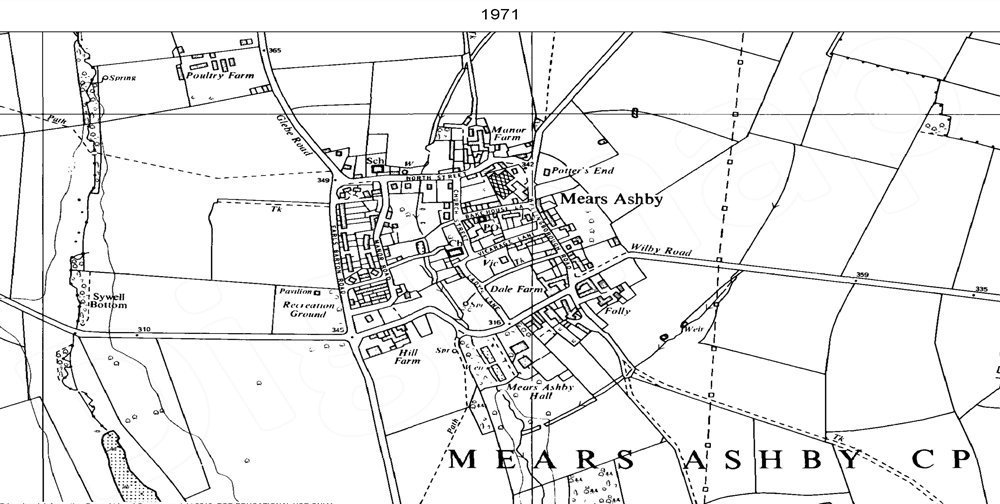

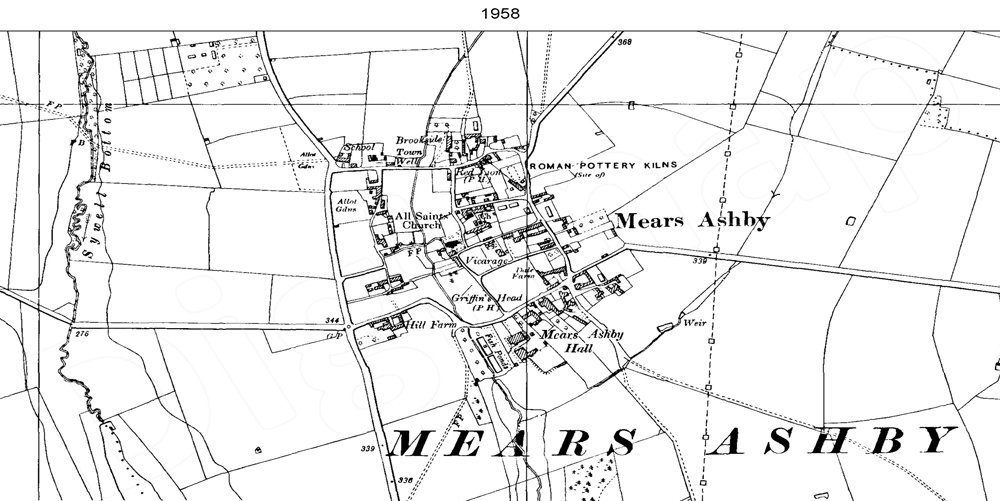

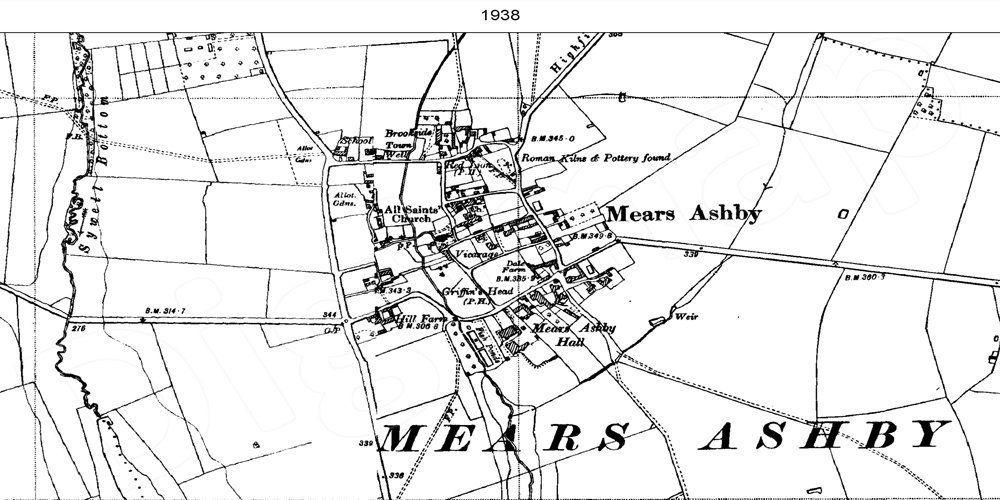

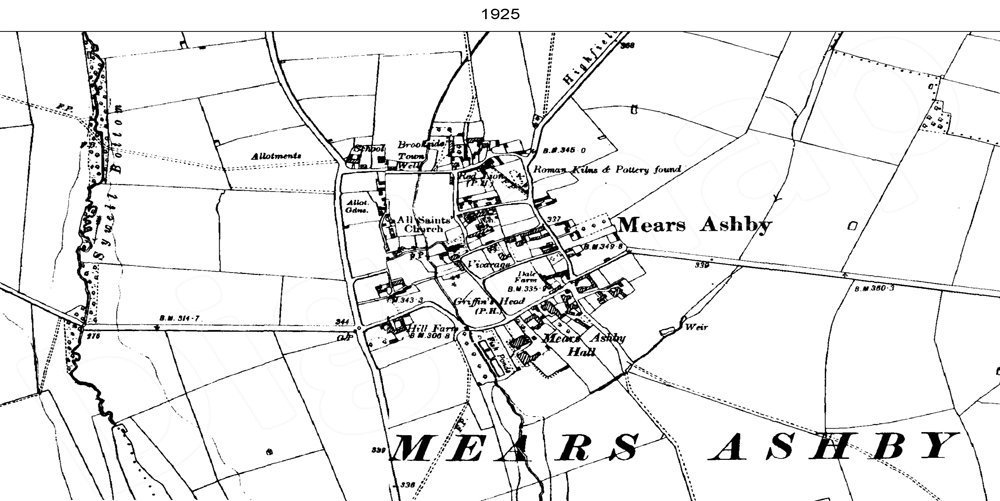

Historic Map Regression

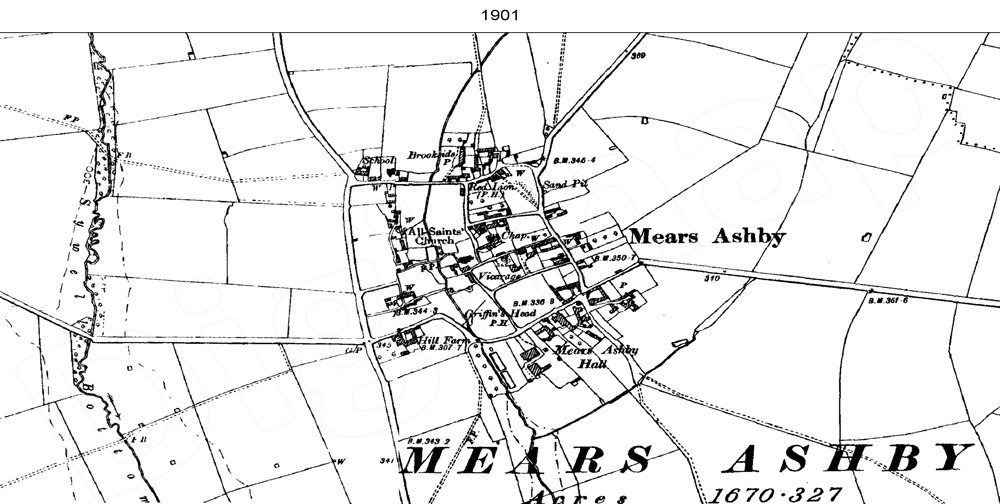

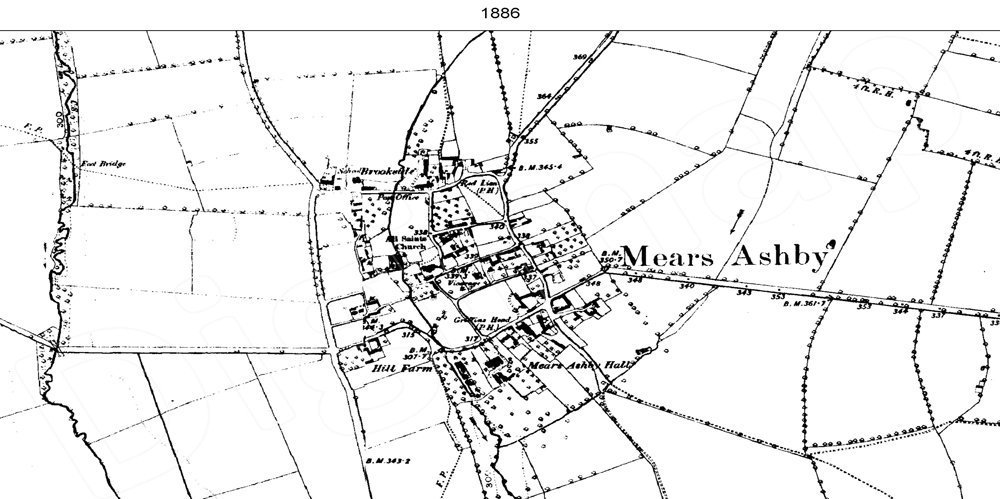

But what if there simply are no old plans to be had? It is very common when researching rural buildings, in particular, to find no old plans at all, in which case we come to rely on the evidence of historic mapping sequences. Map regression is the technique of comparing the same site on a sequence of historic maps, going backwards in time, to work out when the footprint of a building or site was changed or added to. However, maps made before the Ordnance Survey (OS) sequence begins in 1871 can be unreliable, and the earlier the maps were made, the more unreliable and the harder to interpret they can be. For example, early maps are often more pictorial than representative and do not necessarily accurately record the relationship between different buildings either in terms of distance or their size. An early map of Oxfordshire shows random roads in some of the villages which can never have been there and are now interpreted as drafting errors. Tithe or enclosure maps can be helpful, especially if they were drawn up by diligent and accurate surveyors (which was far from being always the case), but often they raise more questions than answers. The OS sequence is generally accurate and can be relied upon, and show changes between 1871 and 1952, when the maps are carefully compared. Our research at Mears Ashby in Northamptonshire showed us that the part of the farmstead which lay outside the village boundary and was therefore ineligible for conversion to residential accommodation actually contained the oldest buildings, which predated both the threshing barn and cattle sheds. This meant that its retention was important in terms of understanding the history and development of the farm, and this argument won over the local authority who consented its conversion to a house despite being technically outside of the village.

Primary Research

No research project would be complete without a trip to the local archives, which normally includes a telling-off from the fierce archivist for some minor infringement of their rules about the number of items which can be viewed at any one time or the use of pencils. Local archives often contain a wealth of information but finding it can be extremely difficult. Archive catalogues are often not online, meaning the only way to search is manually through the index boxes at the archive. Even when catalogues are online finding the right information – and indeed guessing the right search terms – is no easy task. Sometimes there are multiple local archives, due to county boundary changes, and sometimes there are multiple types of archives, for example when researching churches. A key problem for very significant buildings, or those by important architects, is that there is too much information and extracting what is needed for the project without getting lost in a wealth of paperwork, can be challenging. Most researchers find primary research the most exciting part of a project; finding previously unknown plans in New College Archive which showed the original layout for a building we were researching on Oxford High Street was rather like having Christmas in June! When researching a major townhouse on St James’s Square in London, we found in an archive in Wales, receipts from the 1770s showing the paint and fabric, which were bought to decorate the house, and being able to handle such items and include their detail in our work is a privilege.

Other types of primary evidence may include probate inventories, wills, deeds or court judgements. Whilst we only rarely use these, as they tend to offer little concrete evidence about the fabric of a building, they are sometimes useful, for example when trying to determine when a specific alteration was undertaken and by whom or an early layout of a building.

Written Evidence

The list description, if there is one, is often a good starting point, but many of the historic buildings that we work on have either very short or surprisingly inaccurate list descriptions. A variety of written evidence, such as sales particulars, write-ups in Victorian trade magazines such as The Builder or articles in Country Life, where they exist, can provide excellent information about the building at a given time. Sometimes photographs are included, which provide further detail about the appearance of a house or its rooms at the time the article was prepared. Equally newspaper articles from the time can provide important pieces of information – when researching a building in Brentwood, a colleague had narrowed the date of construction down to a 10 year period. A newspaper article from the mid-19th century described a terrible accident when a workman fell from the scaffold and was killed. Whilst tragic, the evidence did allow an accurate date of construction to be established.

There are a variety of other types of written evidence – for example, The Shell Guides which were written in the 1920s and 30s as guide-books for days out in the car, with detailed suggestions as to where to go and what to see, mainly focussing on attractive historic towns and villages. There are, as well, hundreds of books of architectural history and architects’ biography and knowing where to find the information you need requires familiarity with the literature. However, written evidence needs to be critically reviewed, particularly if it is non-academic text, as it often contains inaccuracies. For example, elements of a building which were intended but never completed can be described as finished in magazine articles and information can be tantalisingly brief or incomplete.

House in Woodstock taken c.1870-1880 but

catalogued as early 20th century (Picture Oxon).

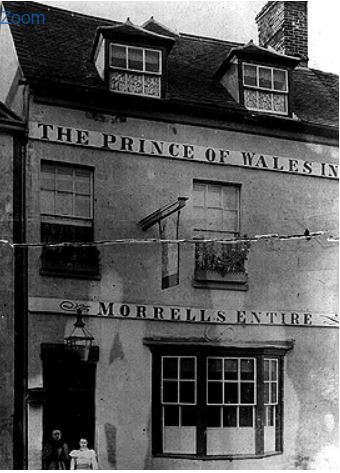

Picture Archives

There are a number of excellent archives which keep collections of historic photos, often catalogued by the individual photographer meaning a search needs to be made of each archive. Piecing together where the photo was taken, which can be surprisingly difficult if the setting of the building has changed drastically, and the date of the photo as they are often misdated on the catalogue entry is required to make sense of the image. Given that photography only came into wide use at the end of the 19th century, historic photos cannot give information about a building or site’s appearance before this time. The excellent Taunt and Packer collections of historic photos were helpful recently when researching a house in Woodstock, and showed that when the photograph was taken the house was rendered rather than having the exposed stone façade which can be seen now. However, the catalogue misdated the photo meaning that the history of the house didn’t make sense; the dress worn by two children shown in the photo allowed us to assert more confidently when it might have been taken, and thus make sense of the house’s chronology.

Modern Plans

Modern floor plans can give a surprising amount of information about the history of an old building. The thickness of walls, for example, can indicate where old structure still exists and where modern fabric has been inserted. Odd nibs or beams can suggest where old walls were removed, and the presence of chimney breasts in a room can indicate how the historic plan-form worked and where the original doors were located. Beware though – modern plans can never give you the whole story and, for example, very thick walls may relate to excessive modern structure rather than the existence of 16th century foundations!

Archaeological Evidence/ Architectural History

Examining the fabric of the building, and relating this to the paper evidence discussed above, is both the best and most difficult part of unravelling the secret life of an old building. Being able to look critically at the materials, construction, joinery, decoration and layout of a building or site, and being able to interpret this in the light of what you already know or suspect, is the key to being able to understand its history and development. However, being able to tell a 17th century frog’s back handrail from a 19th century one is much harder than it ought to be, and both the re-use of old fabric, and copying early designs to make a building look older than it is, are common features that can muddy the waters. Buildings were often re-fronted to hide the extent of later alterations, or altered seamlessly so that the extension reads as part of the primary construction. A recent project in Bourton on the Water revealed that a house listed as being of the 17th century was in fact almost entirely rebuilt and re-fronted in the 1920s, meaning that the list description and previous understanding of the building were both wrong.

Accurately dating and interpreting these features is equally the hardest and most rewarding part of our work. As architectural historians, we painstakingly, visually analyse the built fabric in front of us, in order to draw conclusions about dating and phasing, and for example being able to tell the difference between cornices of the 1840s and 1860s, is both a key skill and our USP.

Our Researchers and Advisers

All of our researchers and advisers are trained to undertake both primary and secondary research and, critically, to interpret their findings and make sense of the information. This is coupled with an academic background in architectural history plus on the job training in the art of being able to decipher the built fabric in front of them, by way of non-intrusive survey and investigation. This allows us to draw clear conclusions about what fabric relates to the primary phase of construction, how the building was changed over time, and what element of this is now of importance or significance. Historic building research requires specific research and interpretive skills, but also something else – tenacity, the ability to think, and therefore research, ‘outside of the box’, and perhaps most importantly an understanding of your ‘gut feeling’ about what a building is trying to tell you.

Conclusion

Whilst understanding buildings is interesting in and of itself, it is the application of this to today’s needs and the future of the building which is so vital in terms of achieving listed building consent or planning permission. Often historic research provides the answer for future development – when a closet wing has been demolished in the early 20th century, for example, and can be rebuilt to provide a lift, or when it is clear that a building has already been rebuilt internally and none of the internal fabric is historic or significant, offering great scope for alteration. There is no doubt that understanding the history of a building or site will help to unlock its future potential as we have shown at countless listed buildings up and down the country. This approach, for example, resulted in the rebuilding of much of Regent Street in central London in the mid-2000s, despite its listing, because our Conservation Management Plan for the area showed that not only had the buildings already been re-built and re-fronted but that the spaces above the first floor and to the rear of the buildings were never considered to be architecturally important. This unlocked millions of square feet of new commercial space and allowed huge investment to be made in this key shopping area in London, with powerful returns for the estate’s owners. All of our advice is underpinned by this thorough understanding of history and development, and because we take great trouble to get this part of the project right, we are well-placed to make recommendations about what could and should happen in the future.