Living Looms: Rescuing Kidderminster’s industry

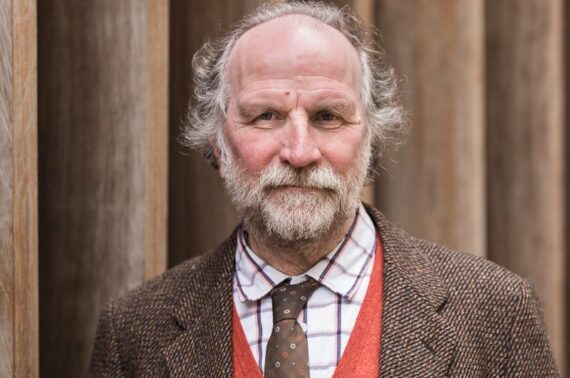

- | Peter Riddington

A bar is attached to each spool wth a ‘comb’ of tin tubes; each threaded with one yard to prevent movement during the weaving. 2008.

In 2007, David Luckham and his partner Mo Mant were commissioned to supply a spectacular carpet for a project in the USA. The client had paid for the work up front and the manufacturer was poised to start production. Then David received a phone call informing him that the factory was to be closed. Faced with a Hobson’s choice, David bought the Victorian looms. Otherwise destined for scrap, these historic machines were the only looms able to achieve the number of colours, fineness of line, and character of a printed tapestry carpet. By saving them, David and Mo took on not just the means of production, but also a considerable liability.

Of all the various consultants and craftspeople Insall has worked with over the years, David is special. The need for high-quality floor coverings is an often overlooked aspect of presenting the most splendid historic interiors; David has helped us find the finest designs and best quality carpets.

From the early 1990s with the Mansion House in the City of London, David has sourced and supplied many of our keynote projects including:

- Liverpool Town Hall: Court Room and Main Reception Rooms

- Windsor Castle: All areas outside of the State rooms

- Royal Albert Hall: Circulation areas and Seating Areas

- Goldsmiths’ Hall: Court Dining Room, Stairs, Lower Ground Floor Hall and Clerk’s Office

- Botley Mansion: All carpeted areas

- Hackwood Park: Ground Floor Curved Hall, Stairs and Landings

- Kenwood House: Deal Staircase

- Arcadian Library

It is sobering that most of the carpets which were supplied for these projects might no longer be possible as the majority of the manufacturers have either gone out of business or have resorted to lower quality production.

‘Foote clothes’

Historically, carpets were a luxury, first seen in English homes in the 16th century. In 1520, Cardinal Wolsey acquired more than 60 oriental carpets and, by 1539, English makers were attempting to copy hand-knotted oriental carpets. When Henry VIII died in 1547, the royal inventories described over 400 floor and table carpets of Turkish origin, with the larger ones for the floor known as ‘foote clothes’.

The 17th century saw the arrival of the first Persian carpets and, later, the collapse of the English hand-knotted carpet industry. By the early 18th century, increasing numbers of imported Turkish carpets were being bought by the middle classes and ownership of them had become de rigueur by the end of the century. With the pace of change quickening, the 18th century also saw the development of the first British carpet ‒ a flatweave Kidderminster double-cloth. Five years later, the first Brussels-weave carpet loom was built at Wilton in Wiltshire and, by 1750, both Kidderminster and Wilton were producing raised-pile carpets on hand looms. The use of carpet was now common, and in fashionable society, favour was for ‘fitted’ Brussels or Wilton carpets and a few hand-knotted carpets. Some architects, including Robert Adam and James Wyatt, designed carpets to be an integral part of their interior schemes, often reflecting the architectural features of the rooms.

The industrial revolution transformed the industry in the 19th century with the patented Jacquard colour/pattern system from 1825; shortly after this, the cottage system was replaced by loom shops. Change followed change and patent followed patent: Whytock’s printed tapestry process in 1834, Templeton’s chenille loom in 1839, a powered Kidderminster weave loom in 1842, and, at the Great Exhibition in 1851, a powered Brussels loom was exhibited which was later bought by Crossleys of Halifax. Other patents included the Spool Axminster (1878), the Gripper Axminster (1890) and the incredible ‘hand-knotting’ looms of Anglo Turkish and the French company Renard. There was also a short-lived revival of the hand-knotted carpet industry.

The 20th century saw a pattern of change and decline akin to most industries. Larger and faster machines were developed but, by the 1980s, overproduction and cheaper imported products created fierce competition. In response, there was a race to the bottom as prices were slashed and standards plummeted. Hundreds of the historic looms which had produced the highest quality carpets were scrapped. Without the looms, the attendant highly-skilled jobs were lost too. Archives of historic designs were dispersed.

Going, going, gone…

To date, the following technologies have been lost forever: Kidderminster looms, Chenille looms, Printed tapestry looms, Anglo-Turkish looms, Renard looms, Worsted wool Wilton looms of two French weaving families. In addition, the following technologies are currently at risk of being lost: the last two small groups of worsted wool Brussels weave and cut pile Wilton looms; and the last group of worsted wool full-pitch spool Axminster looms. The latter category ‒ the Axminster looms ‒ were those purchased by David Luckham.

While tourism connected to heritage brings in approximately £16.5 billion annually, the contribution of historic carpets, and indeed other fabrics and finishes, to historic houses is almost always overlooked. Yet these items provide the setting for all the other furnishings and fittings in a room and are fundamental aspects of the original design of a historic interior. Carpet should be treated with as much respect as family portraits and other items. When a replacement carpet is sought for a historic interior, it should be made in a manner as close as possible to the original design and replicated from original source examples rather than later replicas. This was the approach taken with the second carpet produced following the purchase of the Axminster looms, for the Library of Felbrigg Hall in Norfolk, for The National Trust. Without the looms, restoration projects with this degree of authenticity would not be possible.

Now reaching retirement, David and Mo have begun an initiative to secure the looms for posterity along with, crucially, the skills to work them. The project is to be based in Kidderminster, the historic centre of the carpet-making industry. Donald Insall Associates has been involved in the project in an advisory capacity.

Kidderminster: the town that ‘standeth most by clothing’

In a visit to Kidderminster, some time around 1540, the King’s Antiquary John Leland noted that Kidderminster ‘standeth most by clothing’; its economy relied on the wool trade. By the 18th century the town had specialised in carpet making and consequently grew. In 1951 there were over 30 carpet manufacturers.

Today, it is sobering to tour the town. The likely original home of the rescued looms was the Rock Works, built in 1884 by Richard Smith & Sons, carpet manufacturers. It stands derelict.

The carpet industry in ‘Kidder’ is barely a shadow of its past. Factories ‒ which until relatively recently produced carpets for Donald Insall Associates’ projects, the Woodward Grosvenor works and others, ‒ have now been abandoned. Kidderminster is not unique as a place which has lost its staple industry, but the impact on the town is pronounced. Literally acres of mills and works have been lost and each has tragic human stories attached: skilled workers are no longer able to practise their crafts, and the wider economy declines.

Yes there’s a ‘Carpet Museum’ in Kidderminster, but few carpet companies have the ability to produce carpets. The question has to be asked: ‘isn’t the tradition of manufacturing our heritage, just as much as the bricks-and-mortar buildings within which these crafts were practised?’

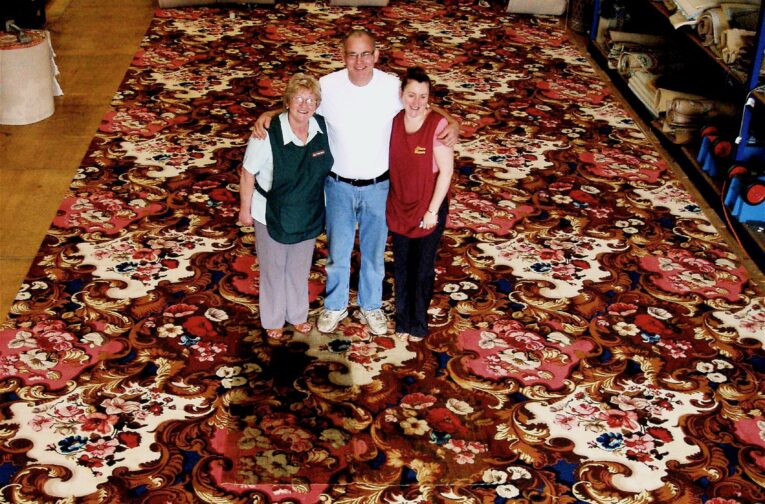

The Team on a half washed original fragment, overlaying the new carpet, 2008.

Living Heritage

The rescued looms are currently housed in an industrial unit in Stourport-on-Severn. The ambition of the Living Looms project is to ensure the legacy of David and Mo’s almost accidental inheritance. It also seeks to prevent further losses of traditional textile products by conserving the knowledge, skills and technologies of historic carpet-weaving for future generations. Secondary to this aim, but still important, is the rescue of the derelict Rock Works. An application for Heritage Lottery funding is being developed.

The project keenly needs support from others. This could involve orders for carpets but, much more importantly now, offers of help in kind from people with time and skills which they can devote to the project. Donald Insall Associates’ Birmingham office has been offering pro bono assistance, but more needs to be done. In saving the looms from scrap, David and Mo’s intervention was critical. Now they need support from elsewhere to spearhead the revival of historic carpet-making machinery and skills, and contribute to the wider regeneration of Kidderminster.

Visitors are welcome at the works, by appointment.

The author would like to acknowledge the advice and guidance of Mo Mant, who contributed to this article. Find out more at: thelivinglooms.co.uk