Vision or Delusion: The Importance of Understanding Significance Before You Get Too Far

- | Helen Ensor

At a recent networking event, I was asked about my view on the development potential of a group of buildings opposite the venue. ‘We need more offices’, I was told: ‘so we were thinking we could create floorspace over there.’

My response – slightly on the hoof and heavily caveated – was that one of the buildings was definitely listed, another one I knew had some considerable interest and might be listable, and some caution should be exercised before the project got too far. I went on that it would be best to proceed by commissioning a piece of work which considered the history, development and significance of the individual buildings and the wider site, so that proposals were brought forward in the full knowledge of what was significant about the place. ‘Ah’, my companion remarked. ‘Yes, but that way we won’t be able to think outside the box. Isn’t it better to start with the vision?’

‘The Vision’ is of course important to any development project, and defining the brief is perhaps the most crucial element of commissioning a new building. The problem is that, time after time, projects come off the rails because the vision is incapable of being realised within the framework of the planning system because it has failed to appreciate the heritage values and significance of a place or site. For example, we are often asked to become involved with a project after a bruising initial pre-app where the conservation officer advised that the project needs to go back to first principles:

- What is the significance of the conservation area and its setting?

- Are these buildings non-designated heritage assets, or are they buildings which could actually be listed?

Understanding significance should not hamper the creation of a robust and innovative – and indeed a visionary – brief but it should lead to an acknowledgement of where harm to the significance of heritage assets may occur, and how to avoid, mitigate or justify (outweigh) that harm.

However, if you don’t understand the significance of a building or place, the risks of drawing up proposals based on a brief which is simply unachievable are quite high. There is often only a fine line between ‘Vision’ and ‘Delusion’. All available best practice guidance documents say that an understanding of heritage significance should come first and should inform the proposals. Where this doesn’t happen, time and money are often wasted, and people become frustrated and their views entrenched.

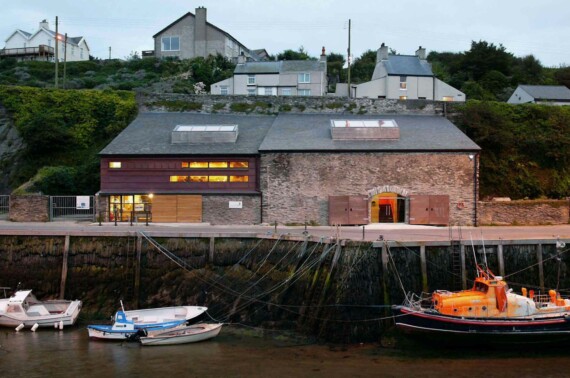

In our view, significance of heritage assets is not something to fear. We can all think of projects where the limitations set by the heritage assets of a site have been the key to great design: Blencowe Hall in Cumbria and the Copper Kingdom visitor centre in Anglesey spring to mind from our own portfolio; or Heatherwick’s Coal Drops Yard at King’s Cross, London, and Zaha Hadid Architects Investcorp Building for Middle East Studies at St Anthony’s College in Oxford. Further afield, one thinks of the Neues Museum in Berlin by David Chipperfield and Julian Harrap or IM Pei’s Louvre Pyramid; or, on a smaller scale, the countless light-filled kitchen extensions that resepct and revitalise Georgian or Victorian terraced houses.

The constraints of a site, including listed buildings, key views and prevailing building heights, often result in memorable and innovative solutions. A building which reinforces a strong sense of place is likely to be more successful in townscape terms than one which doesn’t – and may even result in a process which is quicker, easier and cheaper.