In the Hands of Geology: Wentworth Woodhouse

- | Caroline Drake

The sea route from Cumbria to Wentworth Woodhouse

in the 18th century.

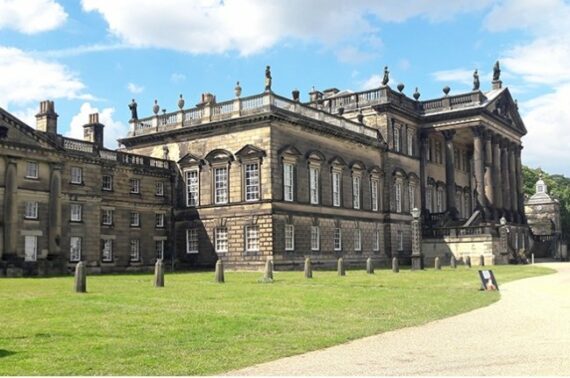

Following cheers at the Chancellor’s announcement of £7.6m in funding, Insall has returned to Wentworth Woodhouse in South Yorkshire to design and oversee two phases of conservation repairs. The earliest parts of the house date from c. 1630 and were built for the first Earl of Strafford. They are incorporated into the rear of the west front ‒ a Baroque building of 1725-1735 built for Strafford’s great, great nephew, Thomas Wentworth, Lord Malton and later the first Marquess of Rockingham. In 1734 construction started on the east front to the designs of Henry Flitcroft. Stone faced, chastely Palladian and rigidly symmetrical, its lower wings were altered and heightened by John Carr from 1782-1784. Measuring 187 metres, it is claimed that the impressive east front is the longest domestic façade in England.

Our task has been making good of the vast expanse of Westmorland slate roofs, which cover 3,250 square metres and are in urgent need of repair, not least because they protect the building’s exceptional interior decoration. The roofs are low in pitch, designed to be invisible from the ground, and set behind a parapet. On a wet day, buckets collect rainwater within the dampened interiors, which are inadequately protected by tarpaulin, introduced to buy some time until full repairs can be undertaken.

Working closely with the new owners ‒ The Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust ‒ and Historic England, Insall has described a first phase of roof repairs, now on site with Aura Conservation. A second more substantial phase of work will start on site soon, including improving the thermal performance of the roofs. Alongside repairs, proposals include the designing of alterations to improve maintenance access of roofs and fire separation measures to help reduce the spread of fire.

Previous interventions introduced mineral wool insulation at the ceiling level of the ‘cold roof’ type without provision for ventilation. This appears to have resulted in condensation leading to timber decay. Our analysis concluded that condensation has contributed to the failure of the slating due to the deterioration of the oak pegs that are fixed to the slates. Consequently, insulation at ceiling level will be removed to prevent further damage to the historic structure and wood fibre board insulation introduced to provide a ventilated ‘warm roof’. Breathability and hygroscopic insulation have been selected over impermeable insulation in order to buffer humidity levels and avoid reliance on barriers to control moisture; the potential failure of barriers and consequential trapping of moisture would present significant risk to the historic fabric. The combination of modern materials and traditional detailing is one example of ‘making better’ at Wentworth.

Supporting tradition

Sourcing traditional materials has become increasingly difficult; as natural resources diminish, methods of extraction and production evolve, and fashions change. But this is a challenge worth rising to in support of traditional crafts and industries, which constitute a tangible and unique aspect of our heritage. The Westmorland slate originally used at Wentworth was quarried from the Lake District beds laid down approximately 350 million years ago. There is no evidence of when quarrying and working of slate first began in the UK, but records exist from medieval times which refer to a slate quarry being worked at Sadgill in Longsleddale, in 1283; records also suggest that some working of blue slate was taking place in Kirkby-in-Furness, in the 1400s. By the 17th century, records document an industry that was clearly already well developed.

Westmorland slate is well known for its green appearance, which generally distinguishes it from the more common blue grey Welsh slate; although Welsh slate is available in a green colour, it is currently only quarried for aggregate, not roofing. From the outset we knew that the procurement of Westmorland slate would be testing, particularly for the programme, because of its scarcity. Early discussions with Burlington Stone ‒ one of the few quarries still producing Westmorland slate to the quantities that would be required ‒ revealed that the project team would need to overcome and manage the long lead-in time of this unique material, which is available only in small batches.

This is a common issue we face as conservation architects. Similar difficulties arose during the re-roofing of Great Court, Trinity College, Cambridge, which was undertaken by Insall in the 1990s. The roofs were covered with Northamptonshire Collyweston slate, which was no longer being mined. New slates therefore had to be sourced, as second-hand material was available in insufficient quantities. After discussion with English Heritage (now Historic England), it was agreed that slates from Cotswold quarries would be appropriate. Initially slate was sourced from Filkins, but later, when this quarry had closed, Naunton slate was used for other roofs.

Our work in Cambridge continues, and with it the challenges of matching the architectural achievements of the past in such a historic city. Happily the Collyweston Quarry has recently re-opened and Insall has negotiated a supply from its first production to cover the roof of 19th-century Bodley’s Court at King’s College. Orders have had to be placed over 15 months in advance of work on site in order to achieve sufficient quantity. Production of the stone traditionally relies on cold winters and a freeze-thaw cycle to laminate the stone ‘log’. Milder winters have required the development of a new technique, and so the stone is now being placed in a deepfreeze. This has sped up production, which can progress throughout the year and not just the winter months. Modern technology and traditional materials are by no means incompatible.

In contrast, the light-green slate band of Burlington Stone’s Elterwater Quarry, in the heart of the Langdale Valley, has been worked since the 1600s and now operates as an open pit. The unique strength of the Westmorland slate produced there can be attributed to its derivation from volcanic ash, which distinguishes it from Welsh slate, which is derived from clay. It is, therefore, an appropriate geological and historical match with the slates seen at Wentworth Woodhouse.

Over the centuries, quarrymen have developed an understanding of how the slate bands in the Lake District run and how to split or ‘rive’ the slate to make and grade roof slates, maximising use of this valuable resource. Skilled quarrymen would ‘rive’ up to two tonnes of roof slates every day. Architects at Insall have visited the quarry, held the slate in our hands, and had a go at ‘riving’ ourselves; we honour the valiant effort and craft involved in quarrying and producing the slates in such quantities and to such a high standard. But how were the slates transported from the Lake District to Wentworth over the period of construction commencing in 1734?

Difficult passage

Slate from Cumbria was often shipped to markets in the south of England. Dressed slate was taken in horse-drawn carts from quarries to a quay at the north end of Coniston Water. Transport from the dressing floor at the quarry would be in a cart or a sledge. Local farmers often supplemented their income by carting goods like this. Slate would be transferred to a large rowing boat to be taken down to a quay at High Nibthwaite at the southern tip of Coniston Water. Today, countless slate fragments can be found at the aforementioned location, testament to this arduous journey. From there, the slate would be taken to the port at Greenodd. Small ships would collect the slate at Greenodd and sail southwards through the Irish Sea, around Lands’ End and along the south coast. The Wentworth Woodhouse slate might have taken this route, sailing the North sea to Humberside. Such a journey would have been long, time consuming and, when French warships were disrupting English vessels along the south coast, dangerous.

Although only 85 miles away as the crow flies, Wentworth Woodhouse was separated from Greenodd by the Pennines. The alternative land route, by pack pony or by coastal sloop, was also fraught with difficulty. Not so with the modern lorries which brought the slate to Wentworth Woodhouse earlier this year.

While transportation is now much improved, we patiently await, in the hands of geology, quarrying and riving of the slate at Elterwater Quarry. Delivery dates have been agreed in batches according to the location and size of the slates, which has informed the sequencing of the works; a first delivery arrived in early May 2018, with subsequent batches to follow later in the year. The largest 20-inch slates for the Riding School, which posed the greatest uncertainty according to the availability of block sizes, are eagerly anticipated from December 2018 onwards. An overall lead-in period of 11 months has been accommodated within the contract period.

In the same way that roofers use slates in diminishing courses to maximise yield, we have specified random widths, striking a balance between best practices outlined in the British Standards and current quarry output to employ the same spirit of resourceful building craft. Slate is a finite resource and salvaged slates will be saved for re-use on other areas of the roofs.

Make your mark

The skilled craftspeople who have worked at Wentworth Woodhouse have been secretly leaving their mark on this historic building for more than 200 years. The Trust invites supporters to leave their own legacy by sponsoring a slate destined for the roof in order to help raise funds. It estimates that up to £200 million will be needed to restore the house, and carry on the tradition. The Make Your Mark appeal asks for a minimum donation of £50 and slates will be etched with personal messages by Paul Furniss, a local contractor from Wentworth, who has worked over a number of years at the house.

If you would like to sponsor a slate and support the repair work to protect Wentworth Woodhouse visit www.wentworthwoodhouse.org.uk